Won Seoungwon received M.F.A. from Kunstakademie Dusseldorf in 2002 and Kunsthochschule für Medien Köln in 2005. She is represented by Arario Gallery and currently lives and works in Seoul.

Won

Seoungwon’s artistic practice begins with the question, “Where do stories come

from?” Her early work My Life(1999) documented the small

objects inside a 2×4m room—pill packets, letters from her mother, socks, and

pieces of bread—through 628 photographs that were then compiled as a single

work, marking the starting point of transforming the most ordinary traces of

her life into a visual narrative. From this work onward, her interest shifted

toward “the life she can actually hold onto,” leading to a belief that a small

room, its objects, and individual memories can form an entire ‘world.’

Thereafter,

‘space and desire’ became the core axis of her practice. In the

‘Dreamroom’(2000–2004) series, she traveled around the world to collect images

that construct the ideal rooms desired by herself and her friends. On top of

real one-room apartment photographs, she overlays landscapes such as swamps,

rocks, and primeval forests to construct surreal environments. Works such as Dreamroom-Seoungwon

(2003) and Dreamroom-Tina(2000) place the narrow,

suffocating spaces of reality against “the landscapes of desire lying beneath,”

foreshadowing the consistent attitude across her practice—seeing reality and

imagination simultaneously.

From the

late 2000s, her subject matter expanded outward—from herself, to those around

her, and then to broader members of society.

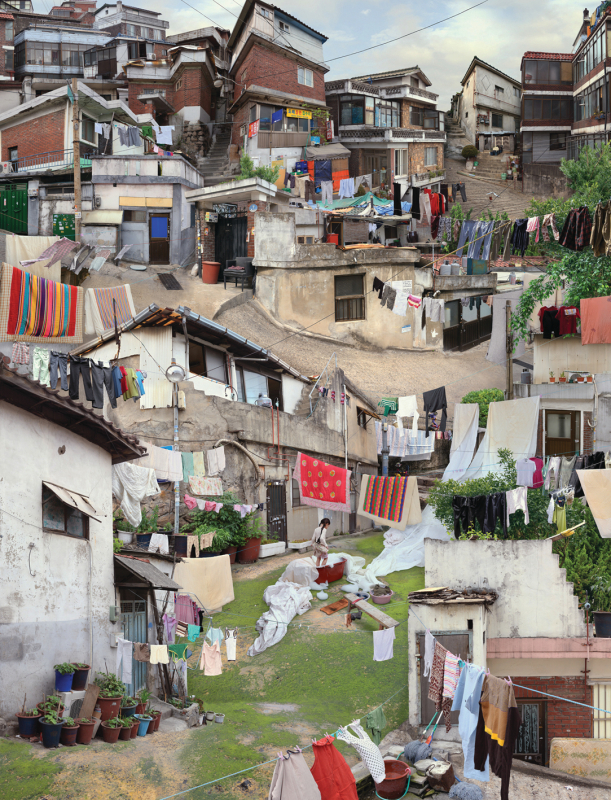

The Tomorrow(2008) series and the exhibition 《Tomorrow》(Alternative Space LOOP, 2008)

begin from daily episodes of family, friends, and colleagues, forming fictional

village scenes where past, present, and imagined future intertwine. The ‘Seven

Years Old’(2010) series presented in the solo exhibition 《1978, Seven Years Old》 reconstructs the

artist’s first experience of separation from her mother through her niece and a

symbolic tree, turning a personal trauma into a narrative of healing. Here, the

young niece stands in for the artist at age seven, and the tree symbolizes the

absent mother, demonstrating how rewriting one’s own life can open up a path

toward empathy.

Since the

2010s, she has expanded from personal narratives to the identities and

emotional structures of ‘social subjects.’ In her solo exhibition 《The Sight of the Others》(Arario Gallery,

2017), works such as The Quarries of Financiers(2017) and The

Sea of Journalists(2017) metaphorically transform specific

professional groups—public officials, journalists, financiers—into rocky

mountains, seas, or clusters of animals, questioning how occupations define

lives and identities. In her recent solo exhibitions 《Freezing

Point of All》(Museum Hanmi, 2022–2023) and 《The Inaudible Audible》(Arario Gallery,

2021), she visualizes superiority and inferiority coexisting within “successful

people,” as well as loose networks and anxious mental states, through motifs

such as icy mountains, trees, droplets of water, and ‘Ordinary Loose Network,’

thus addressing the psychological landscapes of contemporary individuals on a

more universal level.

Formally,

Won Seoungwon’s work is based on digital photo-collage, while in content it

encompasses a hybrid of painting, installation, and literary narratives. She

records subjects with meticulous precision—photographing a single tree in as

many as 60 segments—and assembles hundreds to thousands of images into a single

scene as if composing an “image novel.” While My Life

constructed an installation-like arrangement of objects inside a room, this

spatial sensibility later becomes absorbed into fictional landscapes, making

the picture plane itself a stage and a world.

In series

such as ‘Dreamroom,’ ‘Tomorrow’, and ‘Seven Years Old’(2012), the imagery

always contains “fragments of reality we have seen somewhere,” yet through

their unconventional combinations they form worlds of entirely different

layers. Works such as Seven Years Old–The Chaos Kitchen(2010),

Seven Years Old–Azalea Boiled Rice and Chrysanthemum(2010),

and Seven Years Old–Bed-Wetter’s Laundering(2010) transform

familiar domestic spaces into psychological environments that simultaneously

hold anxiety and comfort, through excessive objects, flora and fauna, and

strangely scaled elements. The narrative is conveyed without text, with each

scene composed like a children’s story—carrying emotional rise and resolution.

Over time,

her collage approach has evolved into more complex and increasingly abstract

forms. In 《The Sight of the Others》, the barren rocky terrain, naked trees, sagging electric wires, and

lightbulbs in The Quarries of Financiers symbolize

professional desires and insecurities, and the circulation of capital.

Meanwhile, works such as The Grass That Used to Be There(2022)

from 《Freezing Point of All》

and Grand Waterfall(2021) and Ordinary Network(2021)

from 《The Inaudible Audible》no

longer reveal specific figures or occupations directly. Instead, motifs such as

ice, droplets, branches, grass, and loose networks metaphorize “poorly handled

inferiority,” “fragile bonds,” and “willpower that grows even in frozen conditions,”

shifting the content toward psychological and emotional planes.

The

distinct sense of estrangement in her compositions stems from technical

decisions. Although based on real landscapes, the scenes are never taken in a

single shot but stitched from many segments with slightly mismatched

perspectives and vanishing points, producing “impossible landscapes.” The near

absence of shadows flattens the image, yet within it coexist multiple times,

seasons, elevations, and distances simultaneously. Tens of thousands of shots,

thousands of selected elements, and thousands of hand-crafted layers—along with

up to ten hours of daily labor—reinsert analog temporality and physicality into

a digitally constructed medium. In this way, form and content are inseparable:

as she describes, “it’s not the forest, but the story of each tree”—the forest

in her work is not a natural sum, but a fabricated relationship formed by

thousands of edited fragments.

Won Seoungwon has established a distinct position in contemporary

Korean photography and image-making by merging staged photography with

narrative-based imagery. Within the strong documentary tradition of Korean

photography, she has built a unique middle ground of “fiction grounded in

reality” by capturing real objects and landscapes and reconstructing them into

newly imagined worlds. Over the past 20 years since My Life,

her work has demonstrated that photography can exceed documentation and become

a psychological and narrative space.

This approach is reflected in her recognition and institutional

presence. Through solo exhibitions such as 《The Sight of the Others》, 《Freezing Point of All》, and 《The Inaudible Audible》, she has examined the

lives of social others, her own childhood anxieties, and the inner structures

of the successful. She has been selected as the recipient of the 23rd DongGang

Photography Award in 2025, establishing her as a key figure in contemporary

Korean photography. Her works are housed in major Korean museums—including the

National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Gyeonggi

Museum of Modern Art, Museum Hanmi, and GoEun Museum of Photography—as well as

international institutions such as the Osthaus Museum (Germany), Santa Barbara

Museum of Art (USA), and Mori Art Museum (Japan), enabling diverse

interpretations of her work across cultural contexts.

Her practice holds strong potential for broader international

reception, thanks to the universal resonance of her themes—superiority and

inferiority, anxiety and relationships, profession and identity, childhood

wounds and adult self-understanding. At the same time, the dense symbolic codes

drawn from Korean professional structures, social systems, and familial

dynamics maintain a grounded locality. It is anticipated that she will continue

to develop “expanded narratives dealing with social subjects, collectives, and

psychological structures,” persistently generating new scenes at the boundary

between reality and imagination.

Won Seoungwon, Ordinary Network, 2021 © Won Seoungwon

Won Seoungwon, Ordinary Network, 2021 © Won Seoungwon

Won

Seoungwon is a natural-born storyteller. This is evident not only when speaking

with her but also in her artworks, which are filled with rich and abundant

narratives. Just as words come together to form sentences, and sentences

accumulate to create a novel, she combines around two thousand individual

photographic images into the construction of a single intriguing story. The

characteristics she had since childhood—talking incessantly when someone was

around and drawing when alone—manifest most vividly in her work today.

Since

her first photographic work My Life in 1999, Won

has spent the past twenty years presenting collage-based works grounded in

photography. She has constructed stories about herself, the people around her,

and the members of our society, often through allegorical or symbolic language.

As more people find her stories compelling and relatable, her narratives have

grown stronger and more captivating. And before anyone realized it, the artist

who once appeared in her show as 《1978, My Age of Seven》 has now reached middle age.

Anxiety at Seven

One

morning, she overslept and awoke to an unnervingly quiet house. Her mother was

nowhere to be found. She checked the kitchen and every corner of the home, but

everything was empty. A sudden surge of fear, anxiety, and the feeling of being

abandoned overwhelmed her. Such a chilling experience is likely not hers alone.

Her exhibition 《1978,

My Age of Seven》 unfolds

against this emotional backdrop.

What can a seven-year-old child do in such a situation? The only possible

action is to swing open the front door and run out in search of her mother. But

the world outside is far from kind to a child.

In

the deepest, most hidden room of the artist’s inner world—the room that led her

to choose the demanding yet fulfilling path of an artist—lived that

seven-year-old child who had experienced the absence of her mother and vaguely

sensed that she had to separate from her and step into the world.

That young

girl filled every spare moment with drawing, and her love for making things

eventually led her to major in sculpture at Chung-Ang University. After

graduation, she left for Germany, where at the renowned Kunstakademie

Düsseldorf she learned, in earnest, what it means to live as an artist.

“My

professor once told me, ‘You are young, so your work will continue to grow. But

what matters is that no matter what hardships come, no matter what criticisms

arise, you must never shrink away. You must be able to explain and justify your

work with confidence.’”

For

Won, Professor Klaus Rinke was a mentor who trained her to speak

about her work with bravery and conviction in front of others. He also played a

critical role in leading her toward the photographic, collage-based practice

she pursues today.

“Actually,

when I first entered the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, I chose installation art.

Though I’m physically small, I’ve always loved large-scale installations and

big works.”

But

that choice backfired. She ambitiously presented a large-scale piece during her

first-semester critique and received praise, but the effort exhausted her so

severely that she had to be hospitalized. Because of repeated hospital stays

and outpatient treatments, she could not properly attend class.

“At

the end of each semester, the professor must decide whether to keep the student

in their class. If you don’t get your professor’s signature, you can’t stay at

the school unless another professor chooses to take you. My professor struggled

for a week before ultimately deciding not to sign. He told me, ‘Large-scale

installation work is too much for you. You’re not strong enough physically, and

you don’t speak well. It will be difficult for you to be an artist. I won’t

sign because I want you to have time to find another career.’ In short, I was

kicked out.”

It

was a moment of complete despair. She returned to her tiny 2m x 4m room and,

before packing her belongings, decided to photograph everything in it. Laying

white paper in the center of the room, she photographed every trivial

object—medicine packets, her mother’s letters, worn socks, bits of leftover

bread—one by one. The images totaled 628. Wanting to see them all at once, she

went early one morning to an empty school building, arranged them on the wall,

and sat contemplating them for a long time. She sensed someone standing beside

her, quietly looking at the photographs. It was Professor Rinke.

After hearing the story behind the photographs, he made an unexpected proposal: “This

is incredibly honest work. Can you come to my class tomorrow and explain this

piece?”

The Beginning of Her Photographic Practice

The

1999 work My Life became the piece that pulled her

back from the edge of a cliff and opened a path toward new possibilities. From

that moment, she began producing digital, photography-based work in earnest. It

also became the turning point that led her to graduate from Kunstakademie

Düsseldorf in 2002 and continue her studies at the Academy of Media Arts

Cologne.

“I

ended up spending eleven years in Germany—from 1995 to 2006—during which I

found the direction of my work as an artist.”

My

Life, a project in which she narrated her own story through her room

and personal objects, developed into Dreamroom, where

she transformed the spaces of people around her into the dream rooms they

longed for. Her friends lived in cramped real-life quarters—one friend who

loved water received an aquarium-like room; another, fascinated by prehistoric

life, was given a room reminiscent of a natural cave; and for herself, always

longing for warmth and nature, she created a room filled with primeval forest.

After

returning to Korea, Won presented 《1978, My Age of Seven》 in 2010, gaining

major attention in the Korean art scene. Her shift from the stories of those

around her back to her own narrative stemmed from a growing psychological

unease—inner anxiety and panic disorder. During therapy and psychoanalytic

sessions, she realized that the seven-year-old child, still crouched in fear

within her, remained unresolved.

“When

I was little, I lived with a large extended family. But when I was seven, my

mother began working. From then on, without understanding why, I waited all day

for her to return. I lived in constant fear of what might happen if she didn’t

come back.”

Afterward,

the themes of Won’s work expanded again—from herself to the stories of people

around her, and ultimately to the stories of broader social groups. Her 2017

exhibition 《The Sight of

the Others》 explicitly identifies

professions—public officials, journalists, professors, financiers—in the titles

of the works, making her intentions unmistakably clear.

The

work The Quarries of Financiers depicts a barren

landscape: dry stone mountains, withered trees, sagging electric wires, and

lamps glowing intermittently. She portrays financiers as people who have the

power to turn stones into gold. The drooping electrical wires resemble fluctuating

stock-market graphs, and the glowing bulbs hint at incoming money. However, the

implication that gold can turn back into stone at any moment contains an

inherent irony.

Her

works embed dense symbolic codes, and deciphering these symbols—connecting

them, inferring them—creates the pleasure of reading her images as stories.

As

for her most recent exhibition, the 2021 series 《The Inaudible Audible》, the puzzle-like

process of reading her stories becomes far simpler, while the visual

completeness of each work becomes far more pronounced. Even the titles—such

as The Weight-Clad Light, Ordinary

Network, and The Blue Potential of a White Branch—are

less concrete than before. Thus, compared to earlier works, narrative elements

are reduced, but their visual impact is immediate and powerful. If one were to

describe the shift in literary terms, it feels like moving from prose to

poetry.

A Work Composed of Two Thousand Parts

“In

the past, a single work might have used around a thousand images; gradually the

number increased, and now it surpasses two thousand. But I no longer want to

count how many images I use. It’s not essential. What matters is the completion

of the work itself.”

Looking

closely at her work, one finds landscapes that appear realistic yet strangely

unfamiliar. The trees, water, grass, and fields that fill the frame are all

based on photographs she physically collects—making them grounded in reality.

But she does not photograph a subject in a single shot. For example, one tree

might be photographed in sixty separate cuts, all to maintain consistent

distance and perspective. Because she stitches these images together, the final

scene carries an uncanny dissonance that does not align with normal optical

perception. It’s the kind of perspective that would only be possible if one

were floating in the air looking down, yet it unfolds naturally across the

image.

“When

I have collected the photographic materials, I sit in front of the computer and

begin assembling each small fragment to construct the story. Through adding,

erasing, and adjusting colors in Photoshop, I create a landscape that both

exists in this world and does not.”

Each

fragment once belonged to a completely different context, but as the tiny

pieces accumulate and merge, they evolve into entirely new narratives. Because

of this process, Won produces at most one or two works a year—the creation time

is extraordinarily long and strenuous.

To produce a single work, she takes tens of thousands of photographs, selects

thousands, and pastes them one by one into a single frame. This collage process

requires months, sometimes years.

Once

she has a concept, she makes a drawing to envision how the final work will

appear. Then she goes out to shoot the images she needs. If a work typically

requires around two thousand photographic fragments, one can imagine how many

total shots are needed—and even then, suitable weather, seasons, and landscapes

must align. The photographic stage alone is extremely demanding, but the

digital process that follows is even more so.

“Working

ten hours a day is normal for me. Sometimes I ask myself, ‘Do I really need to

work this hard?’ But if I start choosing easier paths, I feel like I would lose

the attraction of the work itself.

Life may be hardship—but the process of immersing myself in the world of the

computer, imagining endlessly, and creating that imagination into images,

that’s joy. It’s closer to meditation than suffering.”

Because

she works alone from beginning to end, she is always short on time. She

dedicates as much of her life as possible to her work and reduces her everyday

life to its minimum, living in a simplified, almost ascetic way.

In her words: “My

life may not go the way I want, but my work can. When I sit at the computer, I

live in a world where nothing is impossible. Even if I had all the comfort and

abundance in life, if I weren’t an artist—if I lived an ordinary life—I don’t

think I would be happy.”

Won Seoungwon, Dreamroom-Seoungwon,

2003 © Won Seoungwon

Won Seoungwon, Dreamroom-Seoungwon,

2003 © Won Seoungwon

The Desire for Space

When

examined closely, the long arc of Won’s artistic narrative ultimately begins

with space. Her earliest collage work, My Life,

was born from the 3-pyeong (approximately 9.9 square meters) room in which she

lived, where she photographed and revealed the small, ordinary objects that

structured her daily life.

Later, Dreamroom emerged

from her attention to the spaces of her friends. And the subsequent works,

which unfold across vast and expansive landscapes, likewise reveal how deeply

the artist is drawn to, and desires, space.

“I’ve

always been drawn to things that are big and vast. Reality may impose

limitations, but through the camera I can bring these grand environments into

my world and create expansive realms, sharing the vastness inside my mind with

others.”

Because

she enters the world inside her monitor every day, she says her real-life room

no longer feels small. She begins with a blank white space, and as more and

more fragments accumulate within it, mountains and seas, forests and rivers

gradually appear. Within these paradisiacal landscapes, she experiences a sense

of freedom and happiness. And as this happiness unfolds into vivid, flavorful

stories, the eyes and ears of the viewer, too, are delighted.