Recent

works by Young In Hong, a Korean-born artist currently based in the United

Kingdom, adopt anthropological themes and pluralistic genre formats. In

particular, around the time she was selected as one of the four finalists for

the Korea Artist Prize, jointly organized by the National Museum of Modern

and Contemporary Art, Korea and the SBS Foundation in 2019, she began working

with the history of human labor and animal ecology as central themes.

Given the

nature of these subjects, such works can secure their distinctive artistic

quality only through a process that begins with objective facts, proceeds

through humanities-based judgment, and culminates in the artist’s subjective

interpretation and aesthetic realization grounded in research.

Young

In Hong adheres to this creative process. Above all, she pursues completed

works that not only contain rich layers of meaning but also reveal formal

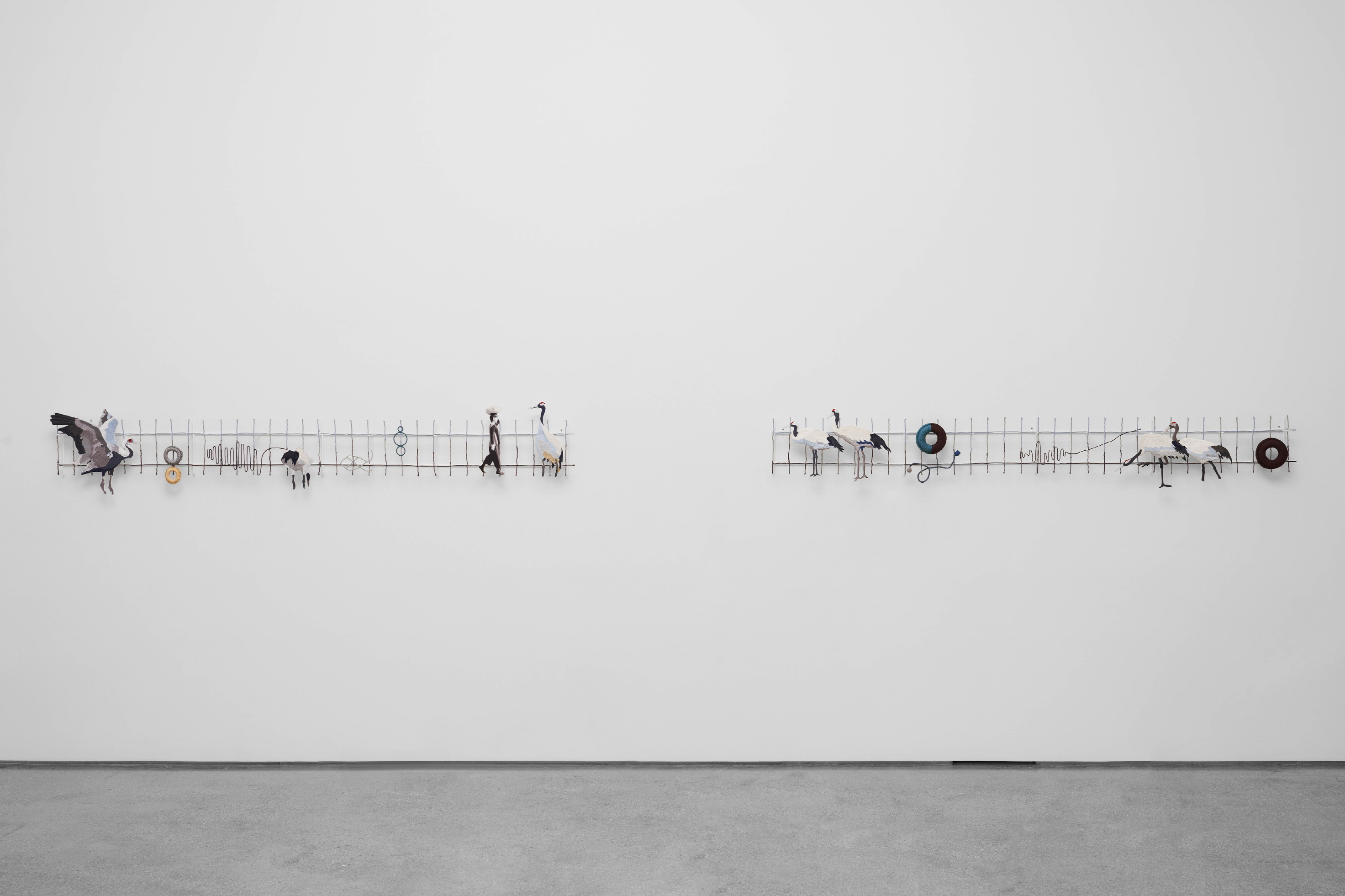

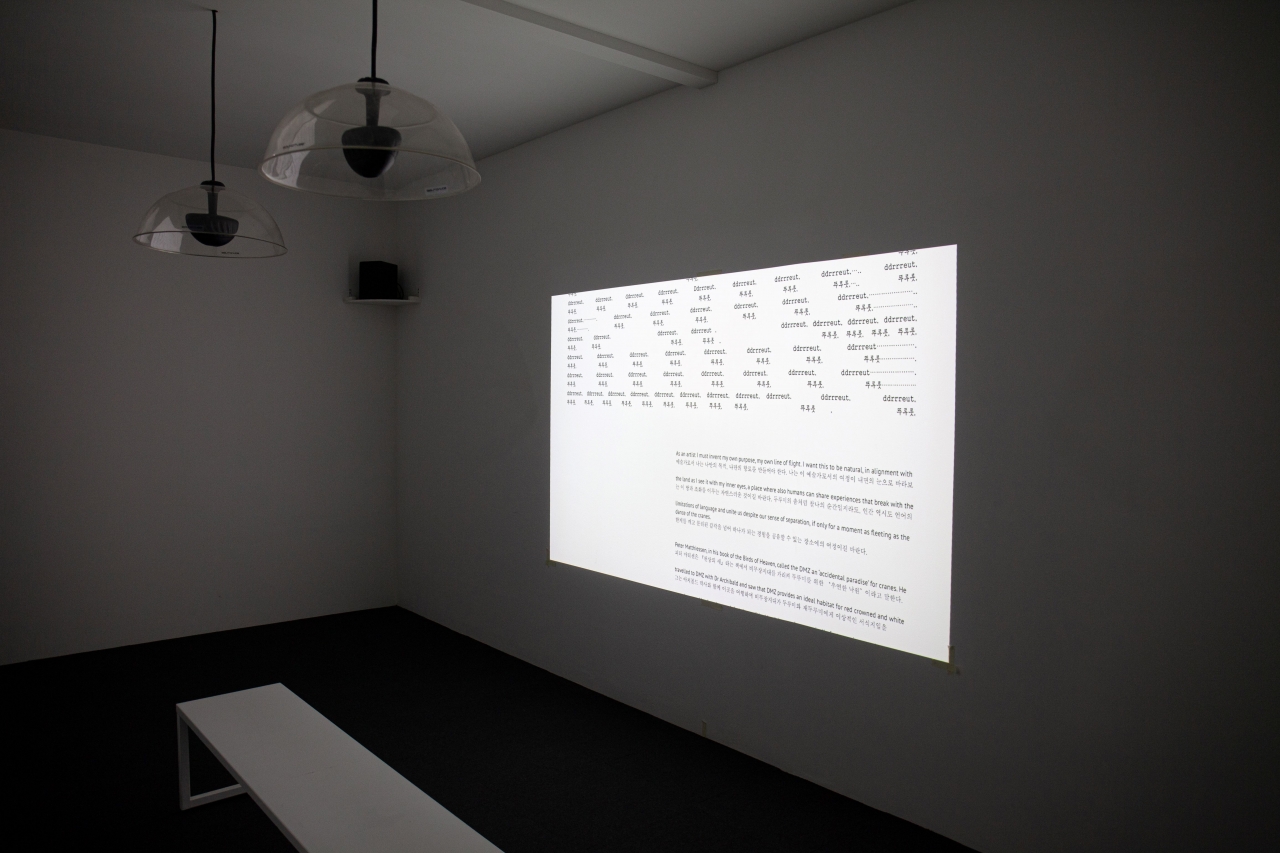

diversity and a synthesis of expressive modes. As a result, her art traverses

genres—embroidered textiles, craft-based sculptural objects, performance, and

sound art—layering media into a condensed field of meaning.

In

particular, 《Five Acts &

A Monologue》 (Art Sonje Center Space 2, May 9–July

20, 2025), her first solo museum exhibition in Korea, presented this

constellation of elements within a single opportunity for engagement—an

exhibition that also functioned as a performance. In short, it provided a site

that moved beyond the static contemplation typical of exhibition spaces,

inducing a complex sensory experience.

As

the exhibition title suggests, the artist constructed a structure in which

monumental tapestry installations, handcrafted sculptural objects, five

performances staged over the course of the exhibition, and a five-channel sound

and video installation interlock like pieces of a puzzle within the symbolic

condition of “acts.”

What,

then, does this physical exhibition structure contain? Embedded like bones

within this sensory field is a theme that viewers may not immediately

recognize—one shaped decisively by the artist’s intent. Across eras, there have

been those whose very existence was ignored within Korea’s power structures,

those who lived as the weak; those who were never considered in the narration

of modern and contemporary Korean history and have reached the present without

leaving behind even the smallest trace of record.

Among them, the historical

contributions and labor of women are of critical importance. Even if not

encompassing the entirety of what these individuals accomplished in their

lives, Young In Hong seeks to place what she has researched and reinterpreted

into the realm of art as marginalized realities of Korean modern history. At

this point, let us briefly detour to another artistic example that offers food

for thought.