In the Name of History

“How

do you remember the scent of your city or hometown? Koo Jeong A is collecting

Korea’s scent memories.”

Ahead of the Korean Pavilion exhibition at the 2024 Venice Biennale, Koo Jeong

A—selected as the representative artist—together with co-artistic directors

Seolhee Lee and Jacob Fabricius, launched an open call inviting anyone to share

memories connected to scent. One participant recorded the smell of coal and

goat milk once encountered in South Hamgyong Province before division; another

recalled the scent lingering inside a traditional mother-of-pearl cabinet,

where fabric bedding and naphthalene subtly mingled.

The participants’ places

of origin extended beyond Korea to North Korea, Japan, Singapore, Croatia, and

beyond. Over the course of several months, more than 600 heterogeneous “scent

memories” were gathered without restrictions of nationality, residence, or

generation, and dispersed throughout the exhibition space under the

title ‘Odorama Cities’. Koo Jeong A, who has long interwoven diverse sensations

from everyday imagery with delicacy, once again expanded the domain of

perception at this biennale, firing a signal flare into a spacetime of gaps and

absences.

The

artist’s synesthetic experimentation dates back to the mid-1990s. After various

trials, the work Odorama(2016), presented at Charing

Cross Station in London, can be interpreted as a prequel to the current

exhibition. The term “odorama,” a neologism combining “odor” and “rama,” plays

a central role once again in the Korean Pavilion exhibition. In the abandoned

subway platform where scent and light once transparently blossomed, the work

now intersects with countless private experiences gathered in 2024, assuming an

unprecedented form. In short, this is an instance in which a social space

constructed from human experience becomes realized as physical space.

Furthermore, the texts accumulated from others’ memories function not merely as

raw responses but as materials for editing and translation. Through

collaboration with the Korean brand Nonfiction, scent keywords were selected:

city, night, people, Seoul, salty smell, hydrangea, sunlight, fog, wood,

earthenware jars, rice, firewood, grandparents’ home, fish market, public

bathhouse, old electronic devices. These individual voices—drawn from

explorations of long-inhabited land—were classified by city, year, and keyword,

sustaining the exhibition as sixteen scents that compress Korea’s modern and

contemporary history into olfactory form: the scent of dawn sea mist, the smell

of rice cooking in an old hanok, exhaust fumes mingled with asphalt, and more.

Scent Infinitely Differentiated

Meanwhile,

wooden sculptures placed inside and outside the exhibition space in the form of

Möbius strips—such as OCV DIFFERENTIAL PEFS(2024)—and

the floor pattern OCV COLLECTIVE SFEP(2024) serve as

foreshadowing devices for a broader historical portrait. The recurring infinity

motif encountered throughout the exhibition becomes a unifying theme that

recalls Ousss, a concept coined by Koo Jeong A. Appearing since 1998 as a

mutable entity traversing various domains, Ousss is both a living

being and the world itself.

Although it lacks a clearly visible form, its

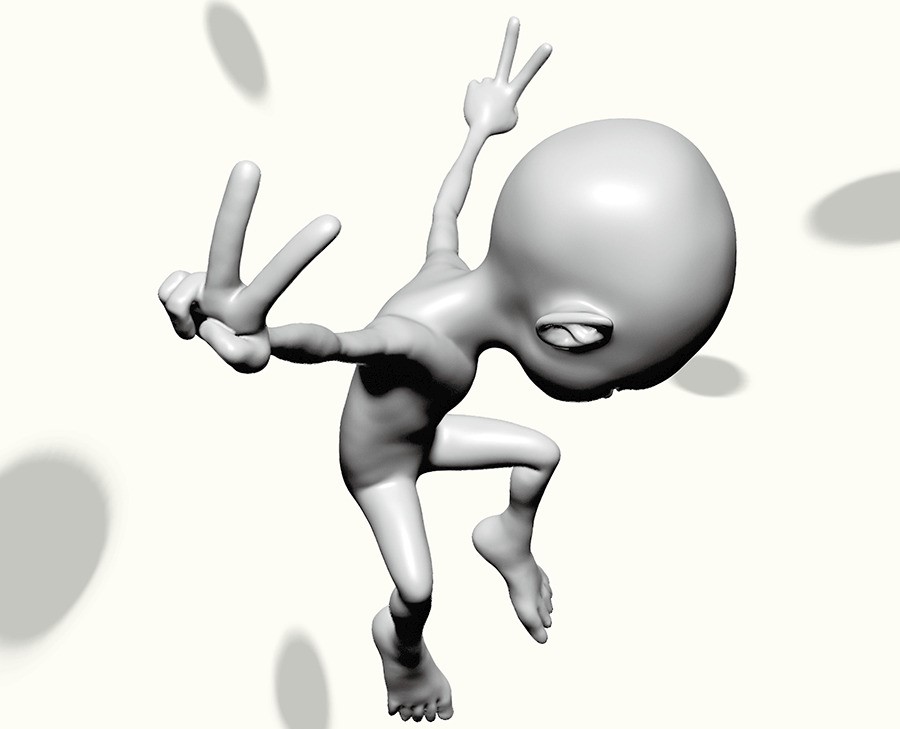

existence is unmistakable. In this exhibition, Ousss materializes

as KANGSE SpSt(2024), a neutral posthuman statue and

diffuser sculpture. Appearing as if it had just flown in and arrived at the

Korean Pavilion, its cartoon-like presence evokes a certain playful humor. The

vapor it exhales from its nose—another olfactory composition made from extracts

such as sandalwood and eucalyptus—overlaps with the foliage visible beyond the

windows, creating a distinctive olfactory experience.¹

In

addition, the sixteen core scents of the exhibition, [OCV RC

1–16] REMOTELY CONNECTED(2024), perform acrobatics in unseen spaces.

Rather than enumerating objects, Koo Jeong A chose to “hide” the scents behind

columns or near ceilings—places that are relatively inconspicuous. Scattered

like an archipelago across the cardinal directions, these unsealed scents

lightly moisten the nose within an open space. The Korean Pavilion website,

accessible via QR codes inside the exhibition, includes a scent index that

functions as a guide. However, identifying specific scents is nearly

impossible.

This appears to be an intentional design, refusing to limit the

imagination of Korea to fixed parameters. Yet the absence of detailed

information about each scent causes the pathways of thought taken by individual

viewers to diverge. Considering the site-specific context of a national

pavilion at a biennale, the historical background implicitly presupposed by the

exhibition—such as modern Korean history—may not apply to non-Korean audiences.

Blaise Pascal once remarked on the “immeasurability” of space: “The eternal

silence of these infinite spaces frightens me.”² For similar reasons, the space

in which scent molecules drift and endlessly expand may remain an unknowable

object, gradually moving beyond the realm of anyone’s experience.

From Gas as Atmosphere to Ground

Can

this olfactory landscape thus formed become a complete mirror of Korea? Koo

Jeong A’s artist statement—“lives and works everywhere,” without reliance on

any specific region—functions both as a manifesto³ and as a concise response to

this question. Here, where borders of nation, generation, and identity quietly

subside, an immaterial portrait of the Korean Peninsula emerges. Yet this

portrait is also an unfinished abstraction. Rather, the artist’s attempt

paradoxically emphasizes that even when traversing Korea’s long history, a work

that fully represents a nation can never be completed.

One might surmise that

the artist’s transnational stance—dismantling the geographic category of the

peninsula through sensation—aligns with an intention to neutralize the

exclusive and modern system of the “national pavilion” at the Venice Biennale.

This does not signify the end of the nation-state, but the once-solid notion of

locality is renegotiated here daily. Perhaps, as Peter Handke wrote

in Offending the Audience(1966), boundaries may neither collapse nor be

crossed—or may never have existed at all. This resonates precisely with the

overarching theme of this year’s biennale: “Foreigners Everywhere.”

On

the way out of the Korean Pavilion, visitors once again encounter foliage.

Sunlight flowing through the open doorway and wind that has traveled across the

northeastern Italian sea slowly erase the traces of scent. Yet the dense forest

aroma encountered near the exit continues strangely into the Giardini park

itself. The boundary between inside and outside—once believed to be

definitive—proves indistinct. In this way, the gaseous mixture of inner and

outer scents becomes the underlying medium supporting the exhibition as a

whole, rewriting the place called the Korean Pavilion.

Each time viewers pass

through, the exhibition halts them momentarily, breathing time into which fixed

concepts may be dismantled. Thus, the space presented by Koo Jeong A this year

is no more than a temporary station. Where, then, does the invisible entity

beyond territory—the one the artist speaks of—lead us? Gazing toward a place

long out of reach, we can only set one foot each at the starting lines of the

poetic world and the real world, awaiting another conversation.

Notes

1.

The fact that Nonfiction sells a perfume titled Odorama City Eau de

Parfum for KRW 258,000 also exemplifies the commercialization of

contemporary art through brand partnerships. As Jeong Jun-mo has asked, is the

biennale a “war of money” and a “festival of luxury brands”?

2.

Markus Schroer, Space, Place, and Boundary, trans. Jung In-mo and Bae

Jung-hee, Ecorivres, 2010, pp. 10–11.

3.

Stephanie Bailey, “At the Venice Biennale, immerse yourself in the evocative

scents of Korea,” Art Basel, 2024.