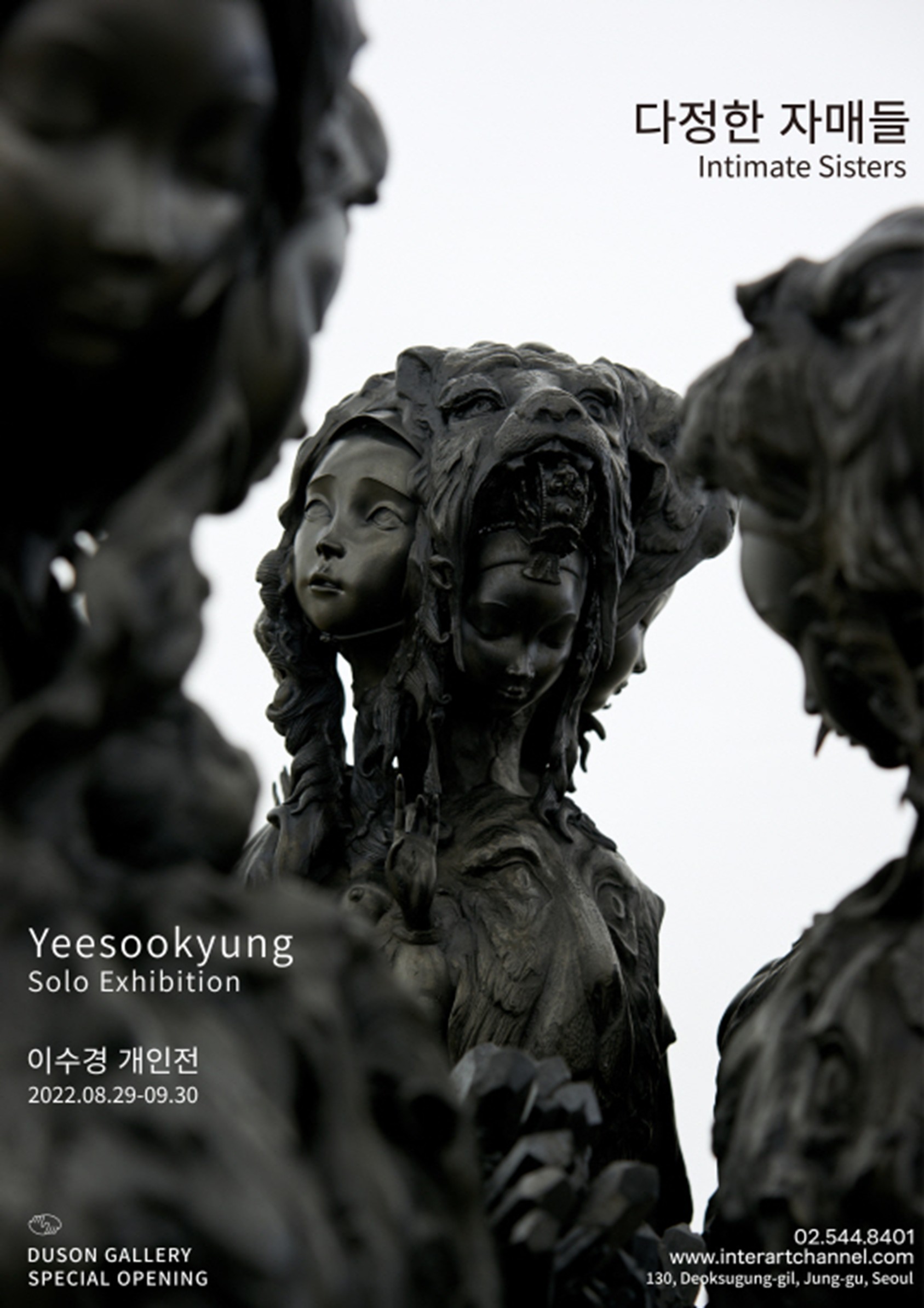

Women

wearing wide, billowing skirts line up and perform a dance in ensemble. Their

hair, adorned with elaborate jewelry, rise up like the spires of temples or the

shapes of flames, below which faces of young girls, innocent and youthful, sit

as if in prayer. They are Princess Bari, Guseul Halmang, Tara (a female

bodhisattva in Tibetan Buddhism), and at the same time, The Virgin Mary.

In her 2021 exhibition Moonlight Crowns, the artist

Yeesookyung selected these women from both Eastern and Western religious and

mythological narratives and depicted them as a sort of deities, arranging them

to present a scene where they cluster in solidarity. A year later, in her

twenty-ninth solo exhibition, she named them ‘Intimate Sisters.’ Here, the term

‘intimate’ conveys a feminine attitude of affection and ‘sisters’ implies

solidarity among women.

While Yeesookyung is well-known for her Translated Vase series

(2002–present), her work has long delved into themes of women’s lives and

identities. In her first solo exhibition, Getting Married to

Myself, in 1992, she portrayed real-world desires and struggles of

women in a cynical manner through a display of photographs in which she played

both bride and groom and glamorous high heels that cannot be worn due to broken

straps .

Yeesookyung belongs to the generation of Korean artists influenced by the

extensive influx of Western feminism beginning in 1988. Unlike the first

generation of feminist artists in Korea who emerged within the Minjung Art

Movement of the 1980s, she embraced feminist art through a more theoretical

approach and a diverse range of themes. As she spent her twenties and thirties

in the 1990s, her experiences of marriage, childbirth, and parenting brought

her to confront the real-world challenges that women face as well as the

complexities of her identity as an artist. In her efforts to reconcile these

aspects, she naturally wove women’s narratives into her work.

In Vases and Crowns, and All Objects, Lies History and Meaning

According

to the artist, the Moonlight Crown series is

described as “works where the crowns have become bodies themselves, too large

and heavy to ever be worn on the head.” Rather than placing crowns, symbols of

power, atop heads, she uses them as pedestals from which fragments of all kinds

of objects sprout up like plants. As a result, the crowns embody the female

figure, as well as the image of a deity. Their surfaces are covered with iron,

bronze, glass, mother-of-pearl, gemstones, and mirrors. Also visible are

angels, praying hands, crosses, dragons, tigers, and Baroque-style botanical patterns.

These fragments are primarily metal ornament pieces used in jewelry that bear

traces of old beliefs but are now abandoned and secularized, having lost their

original place. They hold a similar meaning to the ceramic shards used in

the Translated Vase series, which come from

ceramic pottery that have been destroyed by master potters because they were

deemed imperfect. The artist gathers these discarded objects and shards to

create new forms, new organisms. Most of these artworks bloom into shapes

rounded at the center and are densely packed with objects, which can be viewed

as a symbol of female fertility and abundance, comparable to the Venus of

Willendorf or Rubens’ Three Graces.

Reflecting on the title, the moon represents a feminine space that shines

serenely in the darkness, which stands in contrast with the masculine sun that

illuminates and reveals all things. It is also a mystical presence that

embraces darkness in its shadows and harbors infinite imagination since the

beginning of time. Moonlight, then, functions in Yeesookyung’s artworks as an

energy that allows objects to transcend their past wounds and restore their

sacredness, enabling them to shine once more. This very energy serves to

resurrect a shattered ceramic pot into a complete vase once more, and empower a

forsaken angel to rise above the authority of the crown, reclaiming its

spirituality.

Yeesookyung's creations are predominantly crafted through a meticulous process

of expertly controlling and delicately shaping a variety of materials. Her

emphasis on craft over traditional sculpture and her technique of weaving

together precious gemstones from both the East and West with broken and

discarded objects reveals her intent to transcend not only the traditional

hierarchies of art but also prejudices of the typical world, while

demonstrating her determination to redeem and revive all things beautifully.

Classics of Korean Female Narratives: Princess Bari and Guseul

Halmang

Presiding

over all of this is the face of Princess Bari. The artist frequently depicts

female figures bearing faces of young girls, each of whom can be interpreted as

portrayals of Bari, the heroine of the eponymous Korean folktale. Having freed

themselves from the grime and struggles of the secular world, they come to

signify the idea of purification. Ultimately, through this journey of

purification, they become spiritual beings.

Around 2003, in an effort to awaken her senses, Yeesookyung began creating Buddhist

drawings using cinnabar, which led her to explore religious and mythological

themes. Among these, the Tale of Bari stands out as one of the artist's

longest-standing subjects, first addressed in her 2005 series Breeding

Drawing and later more explicitly in her 3D printing work All

Asleep in 2015. As the story goes, Bari, abandoned by her

parents for being a daughter, embarks on a journey to the underworld to find

the water of life in order to save them. After enduring numerous trials, she

succeeds in reviving her parents and chooses the fate of becoming a mudang (shaman),

who bridges the realms of the living and the dead, human and divine, thereby

becoming the ancestor of all shamans in Korea. The folktale is regarded as a

critique of the patriarchal societal structure and the Confucian ideology

of nam-jon-yeo-bi (male superiority), illustrated

through the life of Bari, who was oppressed simply for being a woman.

Likewise, Guseul Halmang, featured in Moonlight Crown_Guseul

Halmang (2021), stands as a prominent figure in Korean female

mythology. A young girl, abandoned by her parents, encounters a boatman and

drifts to Jeju Island, where she becomes a haenyeo (female

diver). With her exceptional prowess, she harvests abalones and pearls and

presents them to the king, receiving multicolored beads in return. Thereafter,

she became known as Guseul Halmang (Bead Grandmother) and is still regarded

today as the indigenous guardian deity of Jeju, symbolizing fertility and

abundance, and bestowing blessings upon her descendants. While her narrative

parallels that of Princess Bari, Guseul Halmang distinguishes herself by

actively shaping her own destiny, independent of fate. This legend, which

reflects the aspirations of Jeju's haenyeo who led

arduous lives, is reimagined by the artist using old glass buoys and a

3D-printed head of Bari.

Yeesookyung frequently incorporates the imagery of hands in her oeuvre, drawing

inspiration from Tara, the Tibetan female bodhisattva. Tara’s hands, with eyes

on their palms, enables her to perceive all human suffering, safeguarding the

lives of all beings and guiding them toward enlightenment. In Polaris (2012),

the delicate hands of young girls are portrayed in gestures of embrace and

prayer, nurturing both humans and animals. Meanwhile, the women adorned with

tiger skins in Moonlight Crown_Intimate Sisters (2021)

trace their origins to the tiger tribe from the Myth of Dangun. The women of

the tiger tribe, who were overlooked by Dangun, establish their own kingdom and

flourish in infinite proliferation through their solidarity, cooperation, and

mutual care among themselves. The assembly of girls, rising by leaning on each

other's shoulders and adorned with a myriad of women’s breasts embodying the

imagery of a powerful maternal deity, epitomizes the formidable strength of

female solidarity.

Yeesookyung’s recurrent depiction of heroines from classic female

narratives—Princess Bari, Guseul Halmang, Tara, and the women of the tiger

tribe—serves not only to illuminate the discrimination and challenges women

still face in contemporary society but also to celebrate their strength,

resilience, and healing powers in overcoming such adversities.

Affectionate Solidarity: Spirituality Beyond Healing

Yeesookyung

has often been noted for conveying the meaning of ‘healing’ through her method

of filling the geum (cracks) in broken ceramics

with geum (gold). Her recent work on the Moonlight

Crown series, however, appears to have transcended the concept

of ‘healing,’ reaching a higher realm of spirituality.

The artist recalls that while working on the series, she deeply felt that

“spirituality exists equally in all of us.” She suggests that all beings are

interconnected, and therefore, inherently complete. The Moonlight

Crown series communicates a profound belief that encourages us

to let go of the fears and anxieties of reality, as “we are already complete

beings, and our bodies are sacred temples, our spirits the resplendent crowns

themselves.”

The artistic process whereby broken objects intertwine and rely on each other

to form a complete shape embodies a sense of mutual affection or tenderness

that seeks reconciliation over conflict, and coexistence over exclusion.

Yeesookyung's artistic world, which harmonizes the masculine and feminine,

traverses Eastern and Western cultures, and bridges the realms of art and

craft, encapsulates a feminist worldview that cherishes the intrinsic value of

all humanity and all things.