1. The structure of nomination

When

I called her name,

She came to me and became a flower.

- The Flower by Chun-su Kim

Inhwan

Oh presented his work, Name Project: Looking for You at

the Busan Biennale in 2006. He wrote down 20 names on a wall of the exhibition

space and looked for those who shared the names by calling out each one

regularly over an announcement.1) If someone came after hearing

the announcement, he or she would listen to the artist’s description of the

project, have his or her picture taken, and sign the bottom of the photograph.

The 20 names the artist had chosen were among ‘the most common names’ in Korea.

I had heard eight names of people I personally knew very well, eleven if you

count different people with the same name. (One of them had recently changed

the name as the person disliked how common it was.) Even so, how high was the

possibility that some visitor at the biennale, with one of those twenty names,

was there at the exact time of the announcement to hear it?

To

take a concrete example, even if someone named Minjung Kim listened to the

announcement that called her name, it is perhaps not easy to answer the call

with conviction that ‘the name being called now is really my name’ as she

probably experienced similar confusion before since many have the same name as

her. At the Busan Biennale however, the individual named Minjung Kim came to

the artist after listening to the announcement. The name ‘김민정’ (Minjung Kim) written in dull print letters on the wall looked completely

different from the signature of ‘珉貞’ (Minjung) written

in cursive. Afterwards, her name was not called anymore as this common name

became concretized as the one and only individual, ‘Minjung Kim’.

In

the poem, The Flower, poet Chun-su Kim sang about how

amazing the ontological power of “calling one’s name” could be.2) Before

I called her name, she was “nothing more than a gesture” but when I called her,

she came to me and “became a flower.” As such, an indefinite, uncertain being

could become a meaningful being only through ‘my’ nomination. And yet, even ‘I’

am not a complete subject. Only if someone calls my name that “suits my color

and fragrance,” I, too, can become or long to become “the flower.” In this way

the poet scribed, “You for me, and I for you long to become an unforgettable

glance”. When the poem was published, ‘glance’ was initially written as

‘meaning,’ but the poet revised it afterwards. An insignificant being shall be

called by its name, i.e. ‘nomination’ to secure a place in the world. In order

for ‘nomination’ to occur, the subject and the object must exist. The subject

defines the other’s ‘color and fragrance’ and their identity, imparting an

appropriate meaning to the other, and forms a relationship by calling its

intrinsic name. The relationship is not concluded unilaterally but moves in a

bilateral cycle.

The

principle of this bilateral subjective nomination penetrates the works of

Inhwan Oh. It is the artist who calls upon ‘Minjung Kim’ at the exhibition

space but the person who decides whether or not to answer the call or join the

project is Minjung Kim. Only with her participation, the project can be

completed and only through the project, Oh can exist as an artist. Oh’s work is

usually completed by the existence and will of the others in the exhibition

space. Accordingly, the completion or incompletion of his work depends on an

external environment and condition. Even if his work is completed in any way,

it is nothing but temporary and his status as an artist is always unstable and

erratic. Since he decided to work in the Republic of Korea as a homosexual

artist, his life is bound to be insecure and precarious at times. He believes

that his work has to reflect his life as a whole3) which is why

the structure of his work is also unstable and risky. His attitude becomes the

structure of his work.4)

The

structure refers to the method of producing meaning from the action of a work.

This category is distinguishable from any formal style or referential imagery.

Oh’s works do not reveal aesthetic qualities, iconic representation, or

textural narrative. Although his work is at times defined as ‘conceptual art’

that harnesses language and text, his idioms are neither for tautological

analysis of the definition of art, like those of Joseph Kosuth’s works nor for

a self-referential objective like the texts of Lawrence Weiner. If Oh’s art is

conceptual, than it may be closer to the meaning in contrast to the ‘visual’ or

‘formal’ and it may correspond to the institutional critique of the conceptual

art, in the historical context. However, unlike Hans Haacke’s work, however,

Oh’s works are not restricted to debunking the political limitation of art

museums.5)

Oh’s

art is conceptual in that it reveals that ‘meaning’ is not a matter of ‘taste’

but the issues of the ‘power.’ He is careful to not come off as a doctrinaire

artist who makes forays into offering the public “’politically correct’ art or

an authoritative being who considers himself to be a representative of the

minority defiant of the majority. He does not offend by displaying overpowering

spectacles in the art museum in a bid to assert his great cause and also

cautions himself against sentimentalism as he becomes excessively immersed in

emotion, delaying any rational judgment. He leads viewers to engage whereas the

viewers have to act upon their own will. The participants’ identities undergo a

temporary process of transformation within this. They experience cracks in

their self-awareness, distrust in their ability to perceive what they had

believed to be concrete, and grasp the fact that there is no absolutely fixed

identity. As such, Oh’s work is an enactment of the condition of a precarious,

unstable being, fragile individuals, weak subjects, and the state of

incompletion.

2. Individual and Ideology

“Ideology

interpellates individuals as subjects.”

Ideology and the Ideological State Apparatuses (1970), Louis Althusser

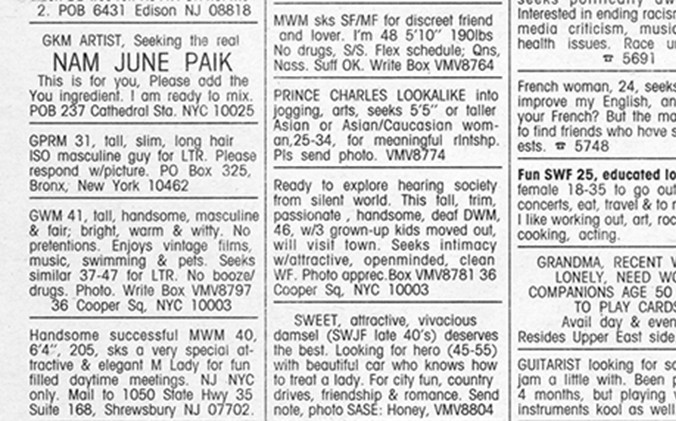

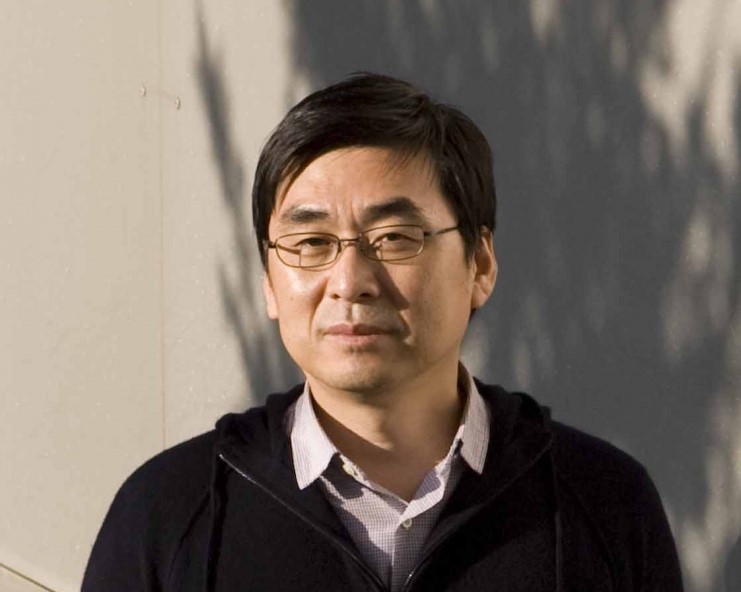

Inhwan

Oh had also worked on a project that involved looking for individuals and

calling their names in 1996. He ran a classified advertisement where he looked

for five artists – Roni Horn, Robert Gober, Nam June Paik, Haim Steinbach, and

Cindy Sherman – in the Personal Ads section of the Village Voice, a weekly

newspaper published in New York. The advertising copy he used was “Seeking the

Real Roni Horn.” Unlike the common names he used in Korea, there are not many

people with the name Roni Horn but matters became complicated with the

inclusion of the adjective “real.” If the famous artist Roni Horn saw the ad,

he might ask himself “Am I a fake?” and if an ordinary person saw it he or she

might argue “the real artist Roni Horn is in me.” The person Oh really found

through this project was not Roni Horn or Cindy Sherman but the artist himself.

He unveiled his identity as a gay Korean male artist (GKM Artist) and came out

through this advertisement. Afterwards, he has been defined as a “gay artist”

above all context and homosexuality has become major keyword that defined his

works.6)

His

personal ad on the Village Voice was paradoxically

a perfect medium for his coming out. “An individual” becomes a meaningful being

when he or she is called by some “voice.” As seen in the poem, The

Flower, any sort of “nomination” always occurs within the

relationship with others, making any “personal relationship” theoretically

impossible. It has thus always postulated the public domain beyond the personal

boundary. A homosexual relationship is an immensely private affair of ‘loving

someone’. However, this has been expanded into a comprehensive social

scientific discourse encompassing issues of gender, human rights, religion,

law, and politics. Louis Althusser defined the public system intervening in the

private domain as the ‘Ideological State Apparatus’ (ISA).7) He

distinguished it from the Repressive State Apparatus (RSA) referring to the

public domain such as the army, prisons, police, courts, and the government. In

contrast, he defined the Ideological State Apparatus as the ‘private domain’

that works through ideology such as family, religion, education, communication,

and culture. The two modes of apparatus share a common goal for the

reproduction of the relations of production, that is to say the sustainable

maintaining of the pre-existent class structure in the frame of capitalism.

While the RSA exercises power through both visible and invisible violence, the

ISA works through interpellation.’8)

Althusser

alluded that “ideology interpellates individuals as subjects.” However, he did

not elaborate upon the difference between the ‘individual’ and the ‘subject’

but simply mentioned that an individual is ‘always already’ a subject. For

instance, an individual is destined to have his ‘father’s name,’ have the

identity anticipated by a specific family, and have his designated social

position from the moment he is born. An individual who is born in this way

adapts himself to the established order that languages and the mass media have

infused in him and unconsciously accepts society’s dominant values and behavior

patterns by internalizing his subjectivity as a sincere consumer in capitalism.

Althusser defined this process or ritual in which an individual is shaped as “a

concrete, personal, and irreplaceable subject” within the frames of religion,

culture, education and family as ‘nomination.’ His ‘nomination’ has an affinity

with Chun-su Kim’s The Flower, in that it is a decisive

phase in which an insignificant being turns into a significant being. Moreover,

this concept stresses the involvement of ideology, one of the Ideological State

Apparatus, in the process that ‘an individual’ as a biological being becomes a

cultural ‘subject’ while being incorporated into a pre-existent social order.

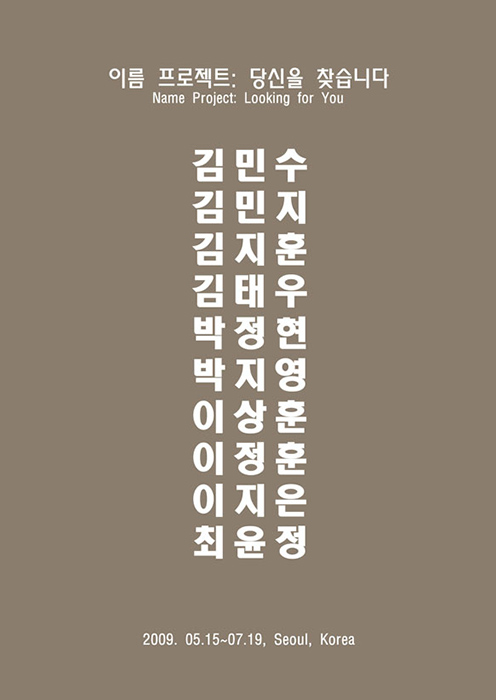

The

structure of ‘nomination’ in Oh’s works apparently reveals the two aspects

mentioned above: a bilateral process in which an individual becomes a subject;

and the existence of Ideological State Apparatus intervening in this process

and working in particular situation in Korea. ‘Names’ are a potent device to

preserve the preexisting order of a patriarchal class society in Korea where

the rule prohibiting marriage between men and women who had the same surname

and ancestral home was abolished in the 21st century. As many as 11 names in

his Name Project finally found their users. They

really were the ‘most common names in Korea.’ But then again, more than 20

million people, almost half of the total population of Korea, use three major

surnames (Kim, Lee, Park) out of the 286 surnames presently in use in Korea.9) Koreans

inherit their fathers’ surnames that come from a pool of less than 300. As for

their given names, one letter is decided by the letter of the names of

relatives in the same generation of a clan while the other is usually chosen

from a letter with an “auspicious” meaning. As a result, we Koreans are all

born with a holy mission: we all have to be agile, upright, and wise.10)

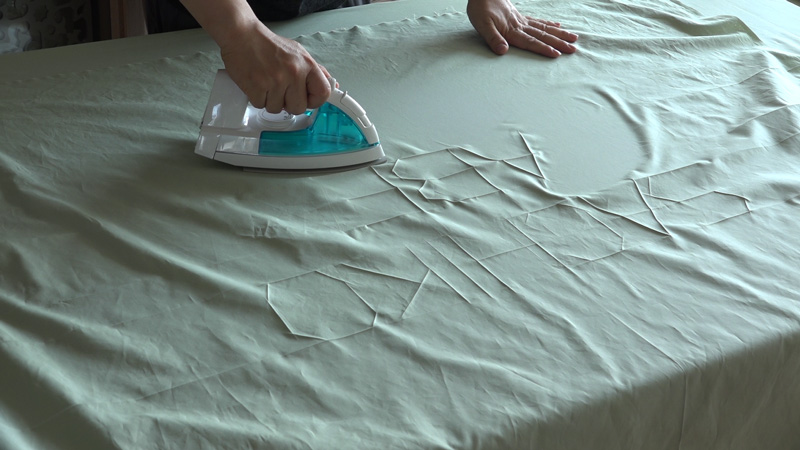

Things

of Friendship (2000-2008) demonstrates how an individual

identity as part of a capitalistic society is defined by ‘industrial products,’

moving beyond family ideology of a patriarchal society. He searches for things

both he and one of his acquaintances possess by searching every nook and cranny

of his acquaintance’s home. He then arranges the discovered objects in order

and photographs them. After returning home he takes out the same objects he

possesses, arranges them in symmetrical juxtaposition with his acquaintance’s

objects, and photographs them. The two sets of ‘things of friendship’ in the

photographs displayed at the gallery are mirror images of each other. Those

‘things’ synecdochically indicate a ‘friendship’ between Oh and a specific

person we do not know. Texts on contemporary art like The World

of Nam June Paik, Art in Theory, and Minimalism

as well as tripods, films, and slide boxes hint at the educational

background and artistic tastes of a figure with the initials ‘KM’ and Inhwan

Oh. However, ‘DD’ and Inhwan Oh who share the same laundry soap, salt, tickets

for the New York subway, and a copy of the Spartacus International Gay Guide

version 2001/2002 are ordinary people who commute by subway, cook food at home,

and at times dream of overseas trip. The person of ‘Inhwan Oh’ appears as a

different man whenever the mirror he faces changes. Things are not an outgrowth

but a producer of his friendship. ‘Friendship’ is an outgrowth of ‘things.’

3. In the name of the father

A

certificate tells me that I was born. I repudiate this certificate: I am not a

poet, but a poem. A poem that is being written, even it looks like a subject.11)

The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis (1981),

Jacques Lacan

Althusser

asserted that the concept of the subject embraces both subjectivity and

subjection.12) This means if someone calls my name, I naturally

identify with the subject of the sentence and unconsciously bring myself to the

position of the subject. The axis of the mechanism of such ‘nomination’ is

language. Althusser’s subject theory formed in language submits to ideological

nomination and combines with Jacques Lacan’s psychoanalysis. Lacan argued that

the subject comes into being through one’s entry into symbolic order, the world

of language and symbols. He expressed this in a terse statement, “I am not a

poet, but a poem.” ‘A signified body,’ namely the subject, is formed as a

result of innumerable writings by others on the sleek surface of the body as a

biological being.

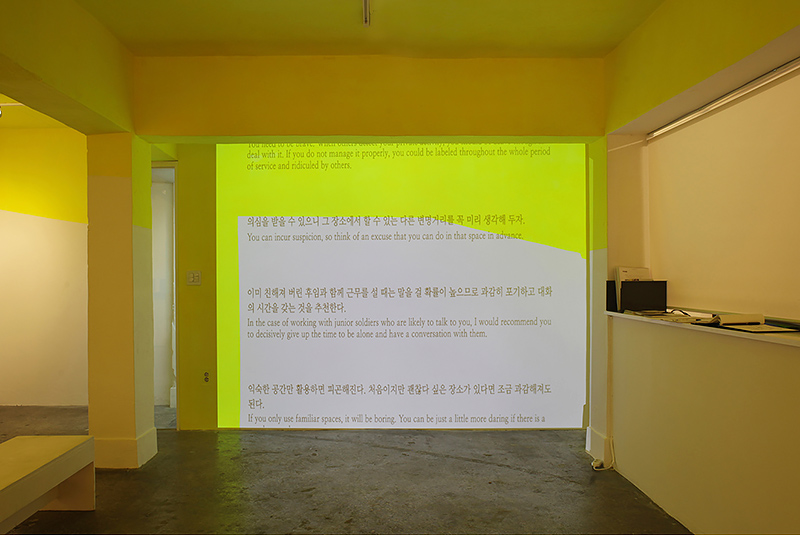

Since

2001 Oh began to install Where He Meets Him at

different venues. He would write numerous letters on the ‘sleek surface’ of the

museum floor with incense powder. The incense powder began to burn as soon as

the exhibit opened, leaving indelible marks of letters like scars by the time

the show came to an end. The letters whose meanings the ‘general public’ cannot

grasp are the names of gay bars and clubs in the city of each exhibition. Art

critic Jung Hyun referred to homosexuality as ‘unspeakable love’.13) Oh

has engraved unspeakable letters otherwise prohibited from being written to

preserve patriarchal order on the skin of the authoritative institution of the

art museum in an extremely physical and destructive manner.

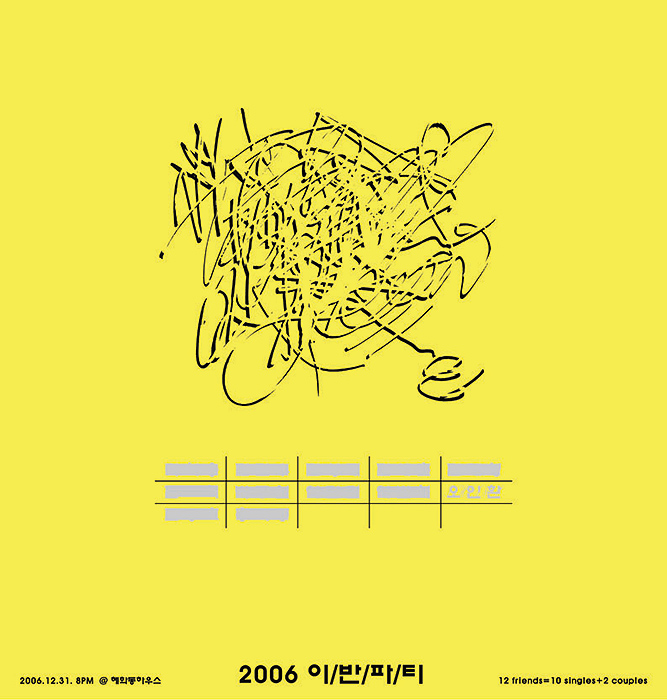

Another Name

Project, Ivan Party is also a work that involves writing

names that should be prohibited or concealed. This work presents the poster for

a year-end party he held from 2004 that he enjoyed with his gay friends.

Participants in the party all signed their names and their signatures

overlapped in such a way that they became unrecognizable. Speaking in the

Althusserian way, they are those who show no response to the Ideological State

Apparatus ‘nomination’. Translating it from a Lacanian perspective, they are

those who do not enter the symbolic order of the dominant language.

Lacan

proposed the subject’s growth and development theory through the

reinterpretation of Sigmund Freud’s Oedipus complex.14) The

classical Freudian psychoanalytic theory states that a young boy desires to

have sexual relations with his mother and feels an impulse to remove his father

in the pre-stage of an Oedipus complex which is composed of five psychosexual

development stages. Afterwards, the boy notices that his mother has no penis

and believes that she was castrated by his father as ‘punishment.’ Accordingly,

the boy suppresses his desire for his mother due to the anxiety that he might

also be castrated (known as castration anxiety), identifying himself with his

father, and projects his feelings of love toward a girl other than his mother.

This is the ‘normal’ growth that Freud denoted. Thus the most important key in

the formation of a boy’s identity is the presence and absence of the penis.15)

Lacan

reconsidered the meaning of the penis as something physical that can be seen.

He implied that the value of the penis is absolute and the patriarchal social

order in which the father’s authority has been firmly established has to be

preceded for such gender difference to be valid. He asserted that the penis is

‘an improper physical symbol’ signifying a prominent social position and

presented the ‘phallus,’ a privileged signifier, to replace it. He meant that

the phallus is not an absolute, elemental thing being ‘signified’ but is the

‘signifier’ whose value is determined by external social factors. He alluded

that the most important device to lend meaning and power to such an empty

signifier is language. Language as a prerequisite for the subject enacts

patriarchal laws, determines an individual’s sexual identity, and subordinates

the individual to the system in the name of the father.16)

As it is widely known, a ‘father’s name’ (nom) stands for the ‘father’s

prohibition’ (non). This is a metaphor for suppression and sacrifice as well as

deficiency and loss innate in the process of subjectification through which one

carries out a transition from a primal being to a meaningful one. Lacan used “a

barred S” ($) as a way of symbolizing the subject who has been alienated and

divided by language (or Althusser’s ideology). Lacan’s subject ($) is by

nature, a ‘precarious, unstable’ being that cannot help but undergo the process

of loss and deficiency. And yet, the real repressed by the father’s name and

prohibition by no means disappears completely. Lacan stated that “something

irregular, unutterable, and ineffable, the ‘aporia’ always appears in

language”. As there are holes in the father’s net of laws, the real has

consistently tried to disturb and overthrow a world of representations. This is

the ‘return of the real.’

Oh’s Looking

Out for Blind Spots is an embodiment of a bright return of the

real. The CCTV cameras look down on the viewers from the high ceiling and keep

an eye on subjects who have adapted themselves to the white tidy space. The

monitors hung on the wall shows the viewers slowly walking around in the

spotless gallery. The individual actually in this space comes to realize that

it is completely different from the one on the monitor. The walls that remain

out of the camera’s view are entirely covered with pink tape. The blind spots,

namely the surplus space not caught by the camera, an area that resists the

gaze of surveillance, and the residual domain that avoids the dominant system

of representation are wider than we expected. The pink tape is an embodiment of

the ‘other’ that has constantly fought for its presence despite being excluded

from the nomination of ideology, has existed without being written as a symbol,

and has been in language without having any property of language. The realm of

the other is more spacious than we thought. That is why anyone can become the

other in the social order of Korea where collectivism and patriarchy are still

solid. Oh did not join any relevant official events and also did not appear in

videos documenting the process of his work because he himself believes that he

is in a blind spot, a surplus space the public gaze cannot catch.

4. HERE, THERE, HOMELESS

Inhwan

Oh has been continuing on with the Street Writing Project since

2000. Oh spontaneously recreated English alphabet with things found on the

streets then took photograph of it. He would then make words by arranging the

photos. The materials he found are nothing more than wastes, including bread

crumbs, fallen leaves, cigarette butts, and broken pieces of glass. They were

perhaps very beautiful, useful, and precious things that had offered pleasure

to their owners before they were thrown away. Oh called their names. He

imparted meaning to them by creating words with the letters and transformed

them into a work of art by displaying the words in a gallery. After Oh leaves

the street, the letters become scattered in all directions. However, they are

no longer the petals withered and fallen from a flower but are scattered

fragments that were once part of a work of art. They form words like HERE,

THERE, and HOMELESS. Perhaps Oh and the rest of us are insecure, precarious

beings floating between meanings ‘without belonging to’ ‘here’ or ‘there’.

1)

For descriptions the works – unless with particular notation – refer

to Inhwan Oh (Seonjung Kim, 2009) and Inhwan Oh’s lecture at the

Seoul National University Graduate School Department of Archeology and Art

History on May 22, 2015.

2)

For discussions on The Flower by Chun-su Kim, refer to Byunghee Son, The

Sorrow of Beings in Chuns-su Kim’s Poems, Korean Language and Literature

Education Studies Vol.50 (February 2012), pp.525-546; Jinhong

Lee, Ontological Illumination of The Flower by Chun-su Kim, Korean

People’s Language and Literature Vol.8 (December 1981), pp.179-190.

3)

Quotation from Inhwan Oh’s lecture on May 22, 2015. Oh has consistently

stressed that the subject of the work should be in accordance with its method.

The explains the reason why he has constantly chosen non-profit spaces to

exhibit his works since his return from the Unites States of America.

4)

The title of this text has been borrowed from Harald Szeemann’s legendary

exhibition titled, Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form. I

appropriated this title with the idea that Oh’s attitude toward his work and

its results are well summarized through this exhibit that puts emphasis on

concept, process, and situation rather than an artwork’s physical existence and

title.

5)

For further discussions on conceptual art, refer to Benjamin

Buchloh, Conceptual Art 1962-1969: From the Aesthetic of

Administration to the Critique of Institutions, October: The Second Decade,

1986-1996 (Cambridge, The MIT Press, 1997), pp.117-155.

6)

Honghee Kim, The Korean Art Scene and Contemporary Art (Noonbit,

2003), p.63. / Seungwan Kang, Made in Korea, New Town Ghost, and Plastic

Paradise, Contemporary Art from Korea (National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Korea, 2007), pp.184-196 / Hyun Jung, Apparatuses for

Rearrangement, Inhwan Oh, pp.50-63. / Misook Song, Unveiling an

Individual’s Identity through Social Context and Cultural Code, 33 Korean

Artists by 33 Best Critics (Kimdaljin Art Research and Consulting, 2012),

pp.96-99.

In an article giving an overview of directions in contemporary Korean art,

Inhwan Oh is considered as specific case for gay artist who appeared in the art

scene in which diversification and globalization progressed rapidly after

debates on postmodernism between the late 1980s and the early 1990s. Youngbaek

Jeon, Sociological Discussion on Cotemporary Korean Art Since the 1960s,

Art History Studies No.23 (2009), pp.397-445.

7)

Louis Althusser, Trans. Ben Brewster, Ideology and Ideological State

Apparatuses, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays (New York, Monthly

Review Press, 1971).

8)

In the sense of ‘calling a name’, the concepts of both Chun-su Kim and

Althusser can be referred to as ‘nomination.’ As Chun-su Kim embraces the

meaning of ‘naming’ referring to giving a name, fit for one’s characteristics

and calling it, its English concept would be ‘nomination.’ Althusser’s

nomination is mainly translated into ‘interpellation.’ For instance, when

someone determined with certain name passes by, calling this person by a name

is a means of ‘instruction’.

9)

Quoted statistical data posted on the website of a site for genealogy, ‘In

Search of Family Trees’. http//www.rootsinfo.co.kr

10)

On the homogenous character of Korean society embraced in the Name Project,

refer to Doryeon Jung, Chance Community, Anonymous Society: On Inhwan Oh’s

Work and Inhwan Oh, pp.92-94.

11)

Jacques Lacan, The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis, Edit.

Jacques-Allan Miller. Trans. Alan Sheridan (New York, W.W. Norton &

Company, 1981), viii.

12)

On the relation between Althusser’s ‘nomination’ and Lacan’s psychoanalysis,

refer to Chanbu Park, Lacan: Representation and Its

Dissatisfaction (Moonjisa, 2006), pp.171-189.

13)

Hyun Jung, Ibid., p.50.

14)

For Lacan’s theory on the subject, refer to Jacques Lacan, Ibid. / Jacques

Lacan, Ecrits: A Selection, Trans. Bruce Fink (New York, W. W. Norton and

Company, 2004) / Sean Homer, Jacques Lacan (London, Routledge, 2005)

/ The Rebirth of Lacan, Edit. Sanghwan Kim & Junki Hong (Changbi,

2009), pp.50-61. / Chanbu Park, Ibid. / Chanbu Park, Non-representational

Representation: Lacan’s Symbolic Real-Ism, Semiotic Studies, Vol. 19 (2006),

pp.223-247 / Myungah Shin, The Father and the Name of the Father: Comparison

of Freud’s and Lacan’s Case Study of Dr. Schreber, Lacan and Modern

Psychoanalysis, Vol.1, No.1 (1999), pp.18-38.

15)

Barry J. Koch, Harold K. Bendicsen, Joseph Palombo, Guide to

Psychoanalytic Developmental Theories (New York, Springer, 2009), pp.3-45.

16)

Jacques Lacan, Ecrits: A Selection, p.67.