An Invitational Exhibition Revealing the Full Scope of Ik-Joong

Kang’s Artistic World

AFKN

broadcasts a program titled ‘Window on Korea’, which offers brief

introductions to Korean culture for U.S. military personnel stationed in Korea

and for foreigners residing there. The significance of this program lies in its

reversal of perspective: it allows Koreans to perceive how their culture appears

through foreign—particularly Western—eyes.

What feels entirely natural within

Korean customs and modes of thought can appear novel or curious to outsiders.

Considering the relativity and specificity of culture, curiosity toward

unfamiliar cultures is only natural, and through such encounters, deeper

cross-cultural understanding becomes possible.

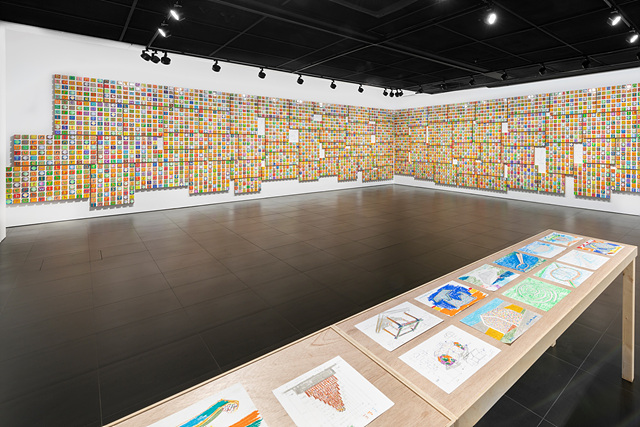

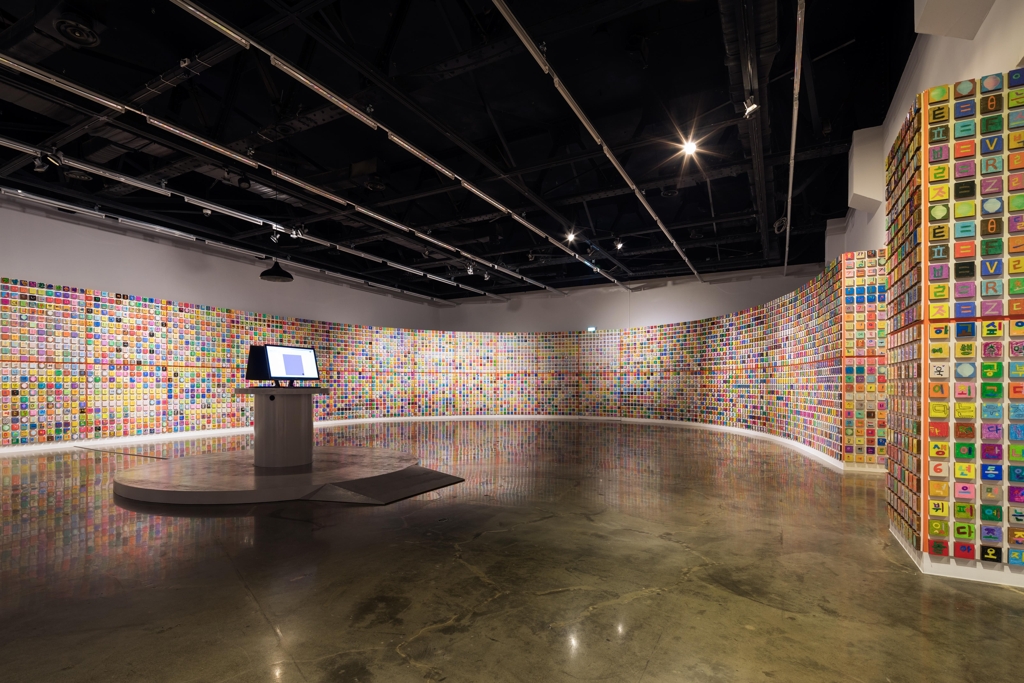

The

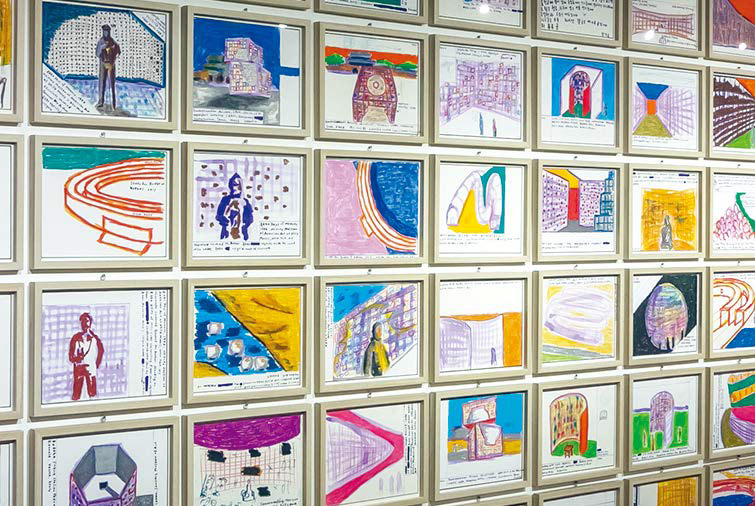

invitational exhibition of Ik-Joong Kang currently being held simultaneously at

three venues—Chosun Ilbo Gallery, Hakgojae, and Art Space Seoul—was striking

above all for its scale. Comprising approximately 50,000 square canvases

measuring 3 inches by 3 inches, the exhibition provided a rare opportunity to

examine the full scope of Kang’s artistic world, which until then had been

known primarily through foreign media.

Kang, a Korean artist based in New York,

first gained recognition among Korean art audiences through his invitational

exhibition at the Whitney Museum held with Nam June Paik. Having majored in

Western painting at Hongik University, Kang moved to New York in 1984 and

completed his graduate studies at Pratt Institute, thereafter embarking on his

full-fledged artistic career.

The

small canvases presented in this exhibition function as Kang’s personal

“windows,” recording impressions and reflections formed while living in the

United States. They also serve as repositories of his inner consciousness.

During his early years in New York, Kang was required to work part-time jobs to

cover living expenses. While commuting between home and work by subway, he

produced small-scale works inside the train cars—effectively transforming the

subway into a mobile studio. This period is vividly captured in the following

passage:

“Ik-Joong

Kang arrived in New York in 1984. For a time, he endured the grueling life of

an international student, working twelve-hour days. In the spare moments he

found time to paint, and it should not be considered particularly unusual that

he created small canvases to carry in his pocket and work on while commuting on

the subway.

Painting was synonymous with survival for him. Through this

process, the now-iconic ‘3-inch by 3-inch’ paintings were born. Today, Kang no

longer lives under conditions that require him to paint in the subway, nor does

he feel compelled to do so. As a full-time artist, he can concentrate on his

work in the studio.

Yet the countless impressions and images that once struck

him as ‘the shock of the new’ at his workplace and on the subway continue to

engage him with the alertness of a hunter. Though his working environment has

changed, the substance of his work has not.”

— Juheon Lee, Fragments of Everyday Life, and Their Accumulation,

Ik-Joong Kang Solo Exhibition Catalogue

Canvases as Windows onto the External World

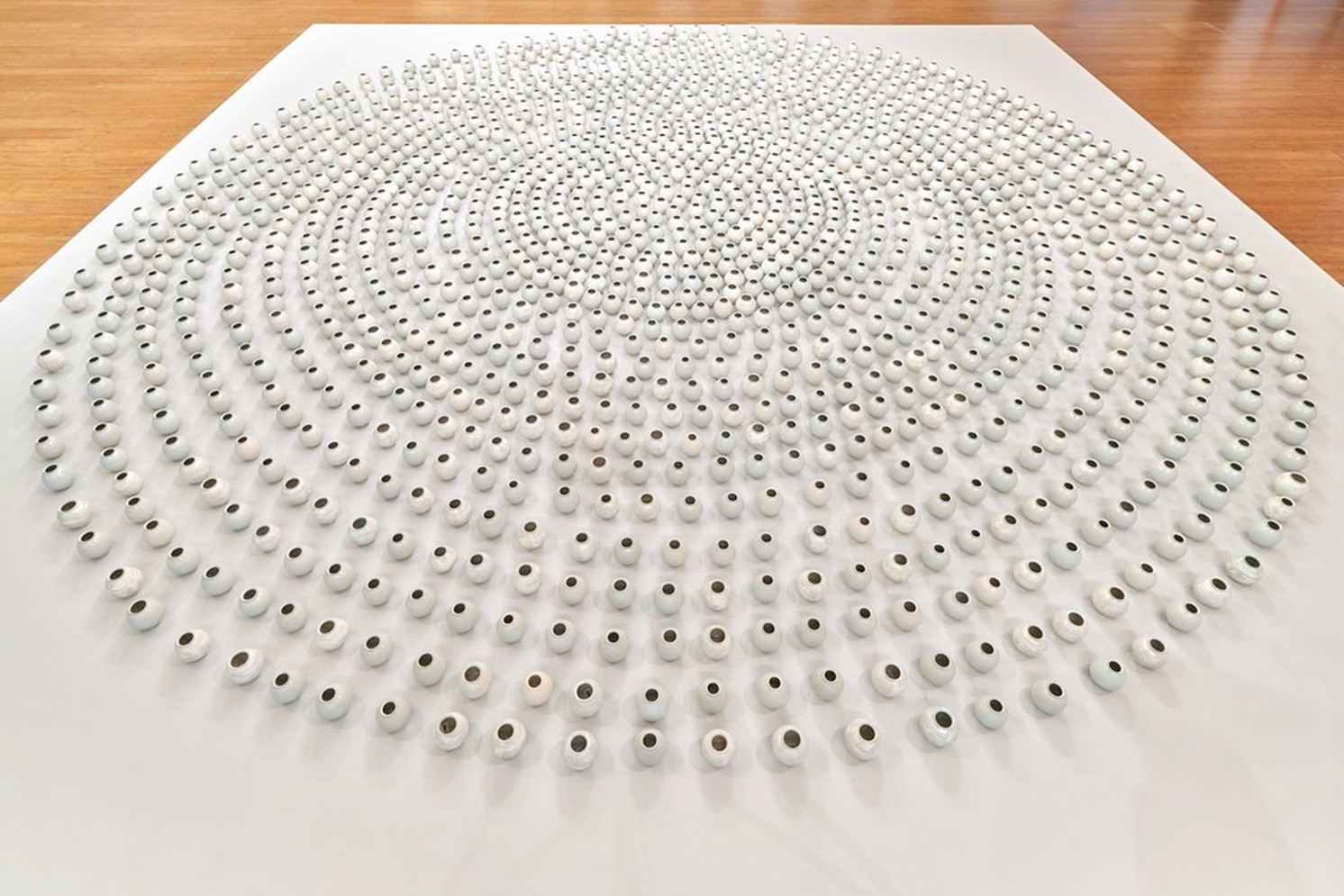

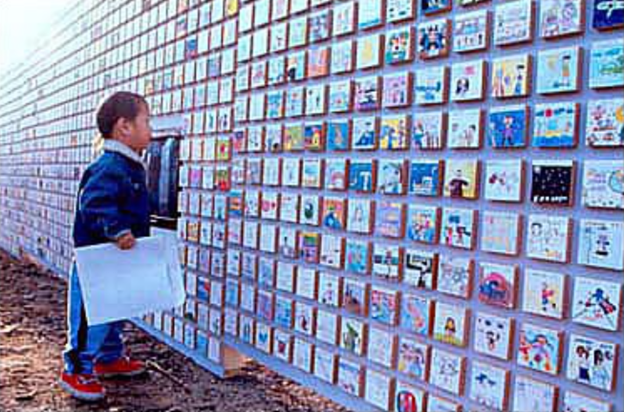

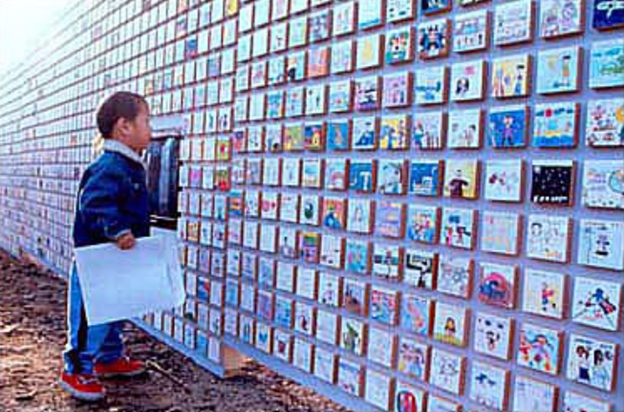

The

catalogue for this exhibition includes a particularly intriguing photograph: a

Japanese samurai examining the landscape by pressing together the raised soles

of his wooden clogs, which form a grid-like structure resembling a telescope.

Much like these clogs, Kang’s grid-based canvases function as windows through

which the painter observes the outside world. Images, objects, and events that

Kang sees, hears, feels, and contemplates in daily life are recorded through a

variety of forms. Minor fragments of everyday experience—encountered on the

street, at school, in the workplace, on the subway, or in markets and

restaurants—are visualized on canvas through Kang’s characteristic wit and

satire.

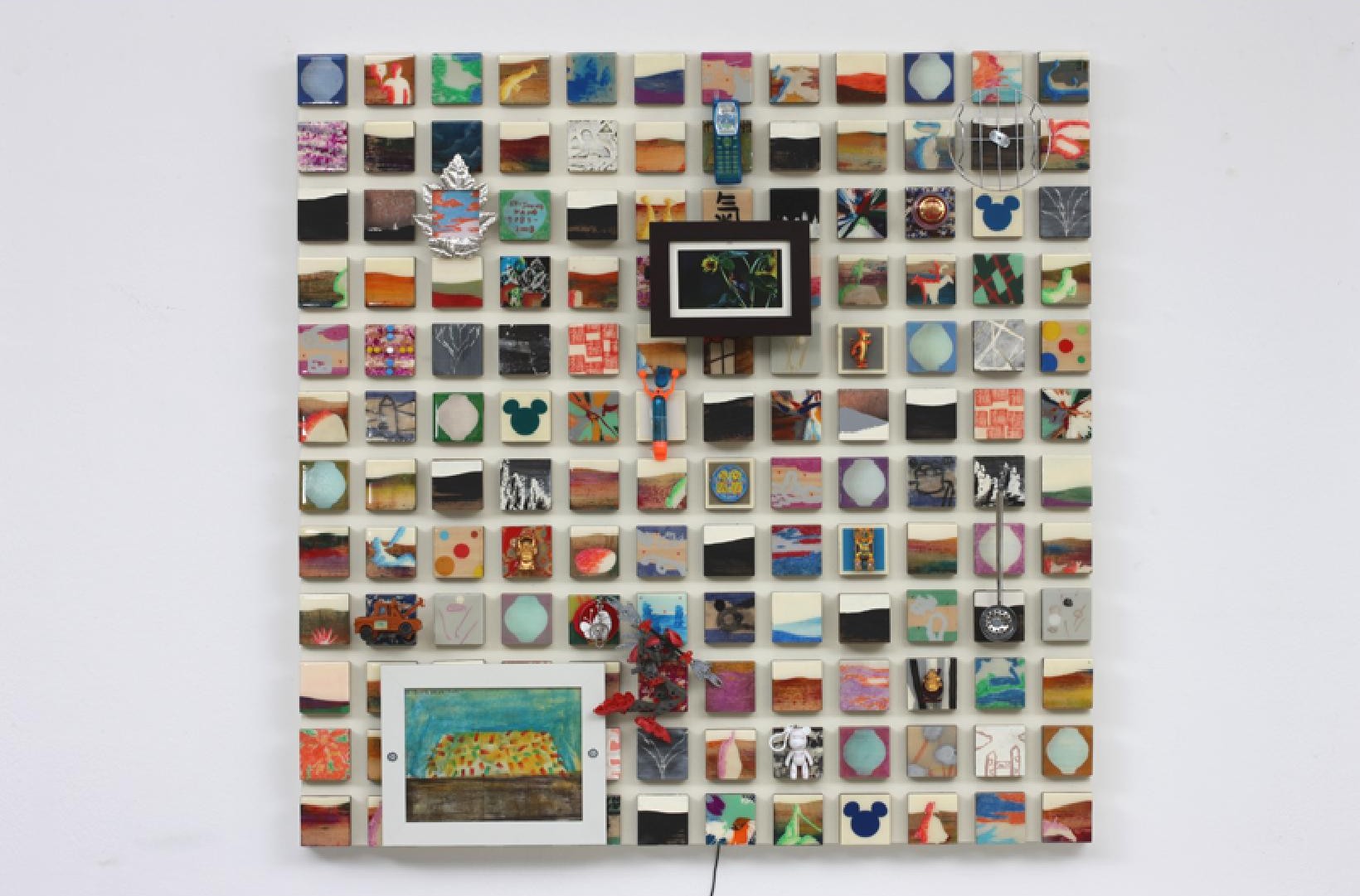

In

transforming objects and events into artworks, Kang does not confine himself

solely to drawing. Various languages—English, Korean, and Chinese

characters—are mobilized, and small everyday items, even fragments of

furniture, are attached as objects. Alongside the ‘happy’ series such as happy

frog, happy bread, and happy

happy sock, sentences like “Someday I will leave myself” also appear.

The countless symbols, signs, and images he creates—combined with numerous

objects he personally selects—offer clues into the flow of Kang’s

consciousness.

Each

3-inch canvas functions independently, much like a freeze-frame in a film, yet

collectively they form parts of a meticulously constructed drama. They serve as

incisive annotations on the complex multicultural reality of New York, a

metropolis where people of many races coexist. The underside of American

society—where racial discrimination, charity and exploitation, hunger and

extreme abundance exist side by side—is dissected through Kang’s distinctive

satire.

His outsider’s gaze upon American society is notably objective, and it

is precisely this objectivity that has contributed significantly to his recent

rise in the United States. When a society incapable of rendering an objective

self-portrait is laid bare by a foreigner, it can only be regarded with

curiosity. Kang’s work titled Research on Restaurant Guides for

Starving Artists conveys, in a bleak tone, the shadowed reality

of New York, widely known as the mecca of contemporary art. It is also a

self-portrait of the artist’s past.

Trust in the Outstanding Imagination of a Master “Mixer of

Cultures”

As

Kang himself has stated, his work resembles bibimbap. This traditional Korean

dish—rice mixed with assorted vegetables—aligns remarkably well with the core

concept of his artistic practice. In bibimbap, the rice placed at the bottom

corresponds to the foundational layer of Kang’s work: the totality of

“Koreanness.” Korean modes of thought, history, customs, cultural practices,

and lived experiences form a dense conceptual mass that constitutes the viral

core driving the expansion of his art.

The

vegetables placed atop the rice are merely supplementary ingredients; as long

as the nature of the rice remains intact, the method of mixing becomes

secondary. Thus, it is possible to argue that the techniques and forms Kang

incorporates into his work are not, in themselves, particularly novel. Rather,

what distinguishes his artistic world is its underlying spirit—the “rice”

itself.

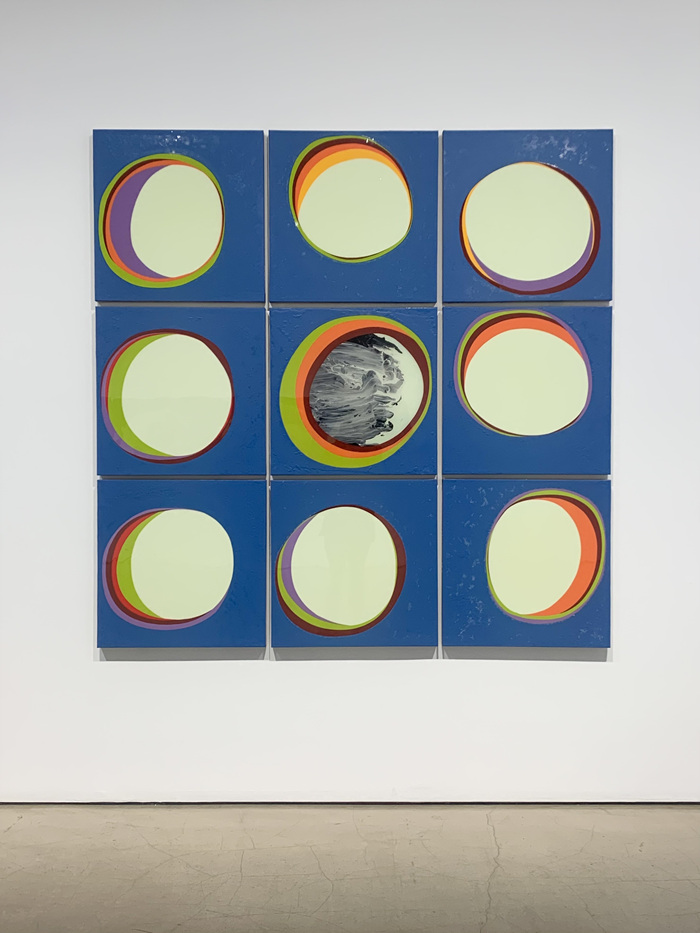

The use of found objects, edible artworks (such as installations using

chocolate), the incorporation of sound, and performance are not what

fundamentally define his practice. Instead, it is the subjective perspective

from which these elements are approached that matters.

In

this regard, Kang’s work exemplifies universality precisely because of his

position as a cool-headed commentator on society. He is unmistakably a master

“mixer of cultures”—someone who mixes rice well.

The

approximately 50,000 works presented in this exhibition are crystallizations of

the artist’s labor and sweat. Each individual piece contains Kang’s personal

memories and impressions of foreign cultures.

The panoramic installations

formed by these works resemble a department store of contemporary art, where

diverse artistic forms converge. One cannot help but anticipate how the work of

this artist—endowed with such exceptional imagination—will continue to unfold

in the future.