I. The Painter’s Lineage and the Formation of Artistic DNA

Ik-Joong

Kang was born on September 11, 1960, in Oksan-myeon, Cheongwon-gun,

Chungcheongbuk-do, as the second son among three brothers to his father Kang

Dae-cheol (1934–1989) and mother Jeong Yang-ja (b. 1933). Although the family

home was originally in Seoul, his mother had returned to her parents’ home to

give birth.

Kang’s father ran a pharmacy in Yeongdeungpo and later acquired a

pharmaceutical company named Daeil Pharmaceutical, which prospered for a time.

However, when Kang was around four years old, the company went bankrupt,

forcing him to spend his formative years in an environment marked by economic

instability—an experience that coincided with the development of his

particularly sensitive temperament.

From

early childhood, Kang was praised by relatives for his talent in drawing. This

may come as little surprise considering that he is a descendant of Gang Hui-an

(1417–1464) of the Joseon dynasty and Gang Se-hwang (1712–1791), both towering

figures in Korean art history. If one assumes that the artistic genes of these

masters flowed in Kang’s blood, his eventual establishment as a painter appears

almost inevitable.

In

1980, Kang entered the College of Fine Arts at Hongik University. Historically,

Hongik University has been synonymous with art education in Korea, producing

the core figures of Korean avant-garde art. From the Informel movement of the

late 1950s to the 1967 Joint Exhibition of Young Artists, and groups such as

A.G. and S.T., many pivotal artistic movements in Korean contemporary art were

driven by Hongik alumni.

While artists from Seoul National University also

participated, Hongik artists formed the mainstream. What unified these

movements was a strong experimental ethos. Avant-garde practice is only

possible when artists possess an intense experimental spirit, and historically,

Hongik University functioned as a gathering ground for such individuals.

When

Kang entered this environment, it was only natural that he would pursue

experimentation in art, drawing upon the traditions established by his

predecessors. However, according to recollections by art critic Juheon Lee, who

entered the university in the same year and observed Kang closely, Kang did not

find university life particularly engaging. Lee recalls the period as follows:

“Ik-Joong

Kang entered the College of Fine Arts at Hongik University in 1980. He had

taken a decisive step toward the life of a painter he had long dreamed of. Yet

student life was not as enjoyable as expected. Above all, he was dissatisfied

with the curriculum and educational content. The environment did not allow for

the free exercise of creativity and imagination. Rather than introducing

diverse artistic currents and encouraging individual expression, many

professors tended to emphasize a single dominant approach.”¹

What

was this “single approach”? One may surmise that it was the monochrome

abstraction prevalent at the time. Beginning in the early 1970s, professors

such as Park Seo-bo, Ha Chong-hyun, Choi Myoung-young, and Suh Seung-won led

the monochrome movement at Hongik’s painting department. While the department

remained a powerful incubator of experimental consciousness, it also gradually

revealed the downside of uniform abstraction.

In such an educational

environment, students with strong individuality either resisted openly or

retreated inward. Ideally, educators should motivate students to express their

unique identities while offering guidance from an objective distance. However,

when practicing artists take on teaching roles, maintaining such distance can be

difficult.

Particularly at Hongik—often described as a battleground of

personalities—the conflict between teacher and student becomes a contest of

force. Those who wish to grow as artists must either quietly endure their

studies and fight fiercely in the art world afterward, or assert their voices

loudly even while enrolled.

By

nature a quiet individual, Kang completed his student years without leaving a

strong impression—so much so that some professors later scarcely remembered

him, despite his eventual rise to stardom.

After

graduating, Kang moved to the United States in 1984 and enrolled at Pratt

Institute. Life in New York—the global heart of art shaped by

multiculturalism—provided him with the foundation for professional success as a

painter. New York is a place that ignites the artistic soul, where everything

seems possible, yet survival demands grueling daily labor.

For impoverished

artists, it is heaven and hell at once. Kang took on various jobs to survive,

including grocery clerk, street vendor selling watches, and worker at a Chinese

restaurant. The 3-inch square works that became his trademark emerged as a

byproduct of this period.

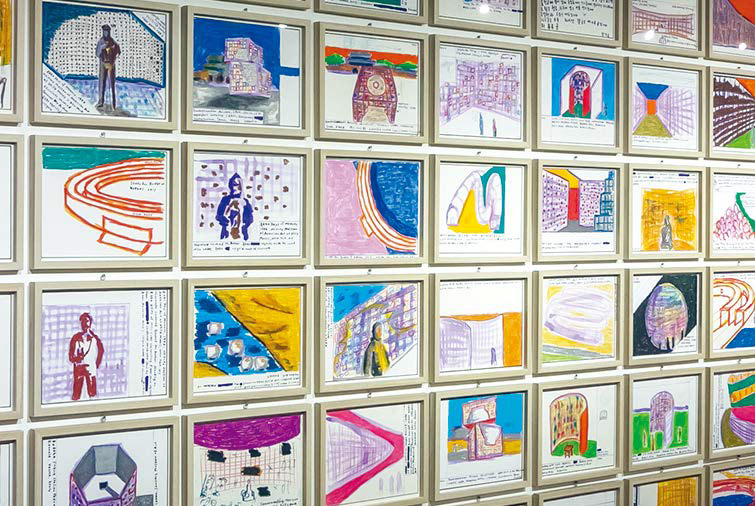

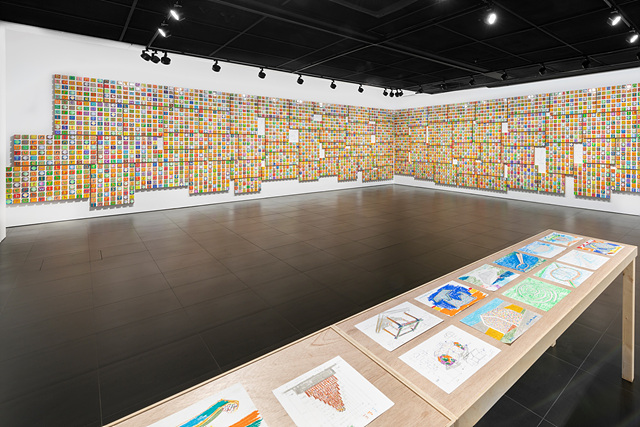

Time

was perpetually scarce. Between studying art and working part-time jobs, Kang’s

days were relentlessly busy. He commuted by subway and sought ways to make use

of that time, eventually settling on a format small enough to hold in his hand.

Measuring 3 inches—or 7.62 centimeters—these works were perfectly sized for

creation on the move.

He painted during subway rides, gradually producing a

vast number of pieces. Kang’s exhibitions often consist of 7,000 or even 14,000

such works, an extraordinary labor by any measure. Some pieces even feature

letters painstakingly carved into hard plywood, requiring immense time and

effort.

Kang

draws material from everyday life. Words and sentences written while studying

English after settling in the U.S. became artworks. Sentences written in blue

and red ballpoint pen on paper were transformed into 3-inch works reminiscent

of the American flag, later exhibited in Seoul. English, Korean, and Chinese

characters appear alongside titles such as happy frog, happy

bread, and happy happy sock, as well as

sentences like “Someday I will leave myself.” Reflecting on these works, I

previously wrote in a review:

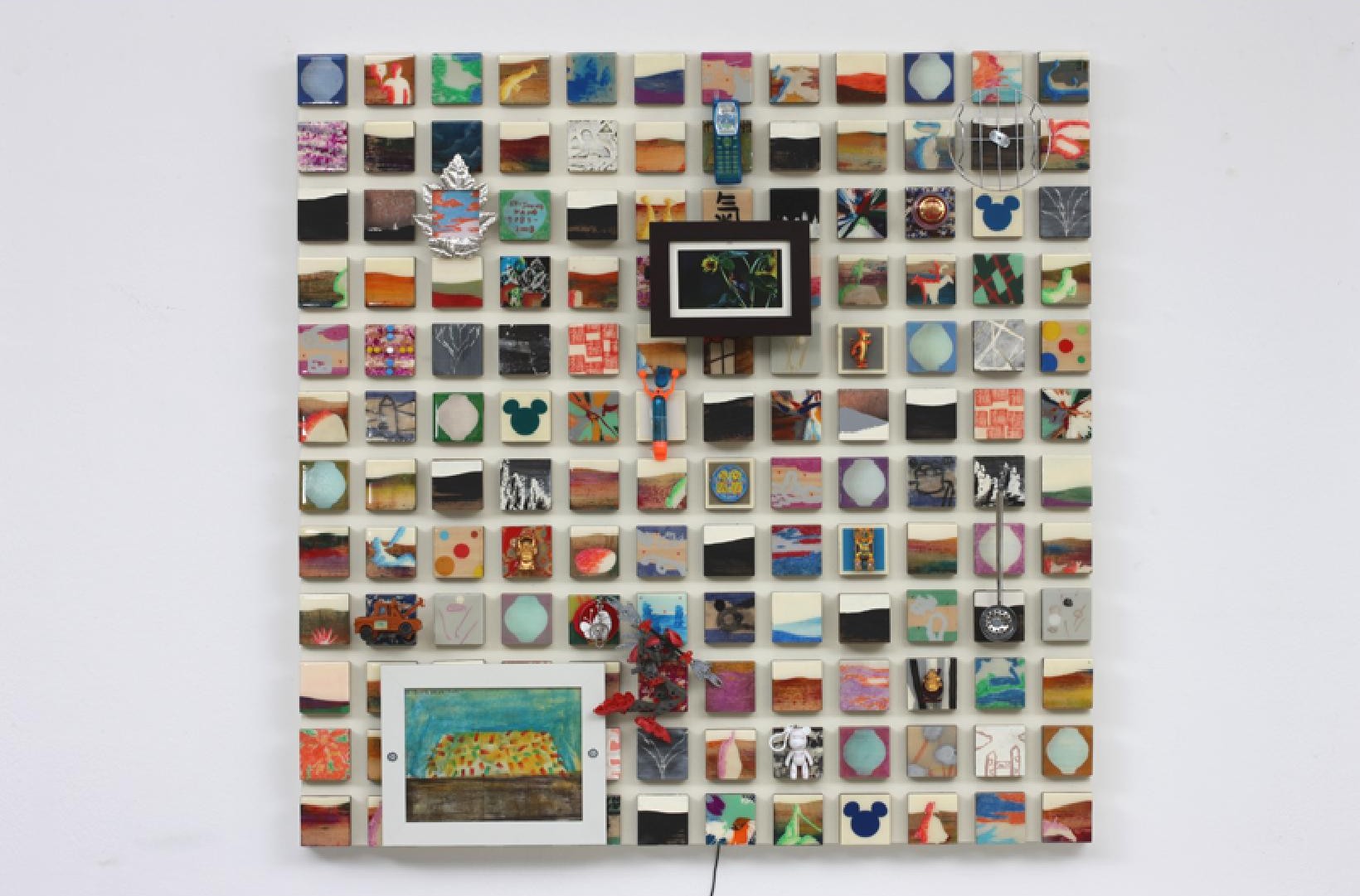

“The

countless symbols, signs, and images he draws—combined with numerous objects he

personally selects—offer clues into the flow of Ik-Joong Kang’s consciousness.

Each 3-inch canvas stands independently like a freeze-frame in a film, yet

together they form part of a carefully structured drama. They function as

incisive annotations on the complex multicultural reality of New York, where

diverse races coexist.

The underside of American society—where racial

discrimination, charity and exploitation, hunger and extreme affluence

coexist—is dissected through Kang’s distinctive satire. His outsider’s gaze on

American society is remarkably objective. Indeed, this objectivity has played a

crucial role in his recent rise in the U.S.

When a society incapable of objectively

portraying its own self-portrait is stripped bare by a foreigner, it can only

look on with curious eyes. Kang’s work titled Research on

Restaurant Guides for Starving Artists conveys the bleak

underside of New York, the so-called mecca of contemporary art, in a desolate

tone. It is also his past self-portrait.”²

That

Kang draws from daily life suggests the inexhaustible and infinite nature of

his work. Sounds collected from reality appear as crucial elements within

installations, functioning like concrete music. By incorporating auditory

elements into what is traditionally a visual domain, Kang achieves a fusion—and

dissolution—of artistic genres.

II. Small Panels as Windows onto the World

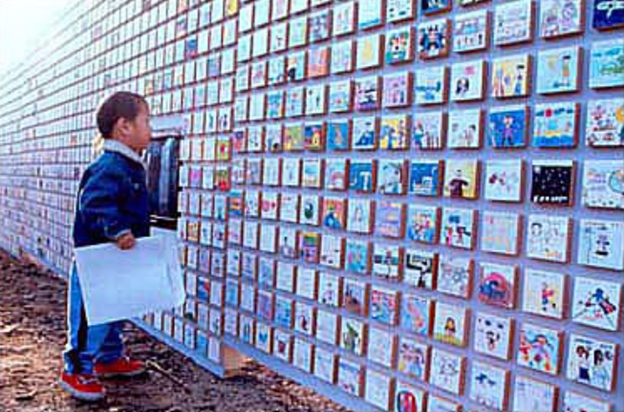

Kang’s

small panels function as metaphors for windows through which the world is

viewed. His first homecoming exhibition in 1996—held simultaneously at three

venues: Chosun Ilbo Gallery, Hakgojae, and Art Space Seoul—was monumental in

many respects.

Following the momentum of his two-person exhibition with Nam

June Paik at the Whitney Museum’s Champion branch in Connecticut (《Multiple/Dialogue》, 1994), Kang’s

small-panel works were introduced to Korea for the first time. The Korean press

responded with widespread coverage. While the attention did not rival that of

Paik’s first return, it nonetheless marked Kang’s official introduction to

Korea as a painter.

The

exhibition catalog featured a particularly intriguing photograph: a Japanese

samurai peering through a pair of wooden clogs pressed together, their

protruding soles forming a grid-like structure akin to a telescope. Like these

clogs, Kang’s grid-based canvases function as windows through which the artist

observes the outside world. Images, objects, and events that he sees, hears,

feels, and thinks in daily life are recorded through diverse forms. Fragmentary

impressions gathered on the street, at school, at work, on the subway, in

markets and restaurants are transformed into images through Kang’s

characteristic wit and satire.

Through

canvases that fit snugly in his hand, Kang observes—and communicates with—the

world. Like Microsoft Windows, or the spiderweb implied by the World Wide Web,

Kang connects with children around the globe through art. Installed in the

visitor lobby of the United Nations headquarters in 2002, Amazing

World followed the participatory children’s program 《100,000 Dreams》 held in 1999 at Heyri Art

Valley in Paju.

When I visited Kang’s studio in New York, it was filled with

drawings sent by children from around the world. At that time, Kang was not

only a painter but also a curator, collecting these individual “windows” via

fax and the internet. These windows were organized into exhibitions and

presented to audiences, creating a cyclical process of exchange.

III. Encounter with Nam June Paik and the Venice Biennale Special

Prize

Nam

June Paik once remarked that behind his success stood Joseph Beuys and John

Cage—a statement equally applicable to Kang. Without his encounter with Paik,

who treated Kang like a son, one might question whether Kang’s success would

have been possible. Their exhibition at the Whitney Museum marked a decisive

moment in establishing Kang’s presence in the U.S. Another pivotal event was

his receipt of a Special Prize at the 1997 Venice Biennale. Commissioner

Kwangsu Oh selected Kang as one of the Korean representatives, enabling him to

receive this honor.

Buoyed

by the Whitney exhibition and the Venice award, Kang went on to participate in

major international exhibitions, including the Gwangju Biennale, further

enhancing his reputation. His small panels—born from the constraints of his

environment—multiplied like viruses, expanding their territory.

Juheon Lee once

described Kang as possessing a childlike innocence, a trait that likely

influenced his later engagement with children’s participatory projects

worldwide. Children communicate transparently, and Kang’s exhibitions involving

children clearly function as bridges connecting the world.

Rather than a linear

system symbolizing adult-centered power, his approach aligns with rhizomatic

thinking—an endlessly expanding network resembling underground roots. Remarkably,

this structure anticipates contemporary social networking platforms such as

Facebook and Twitter. Long before their global spread, Kang had already

practiced such networked exchange through his small panels and their pure

window-like logic.

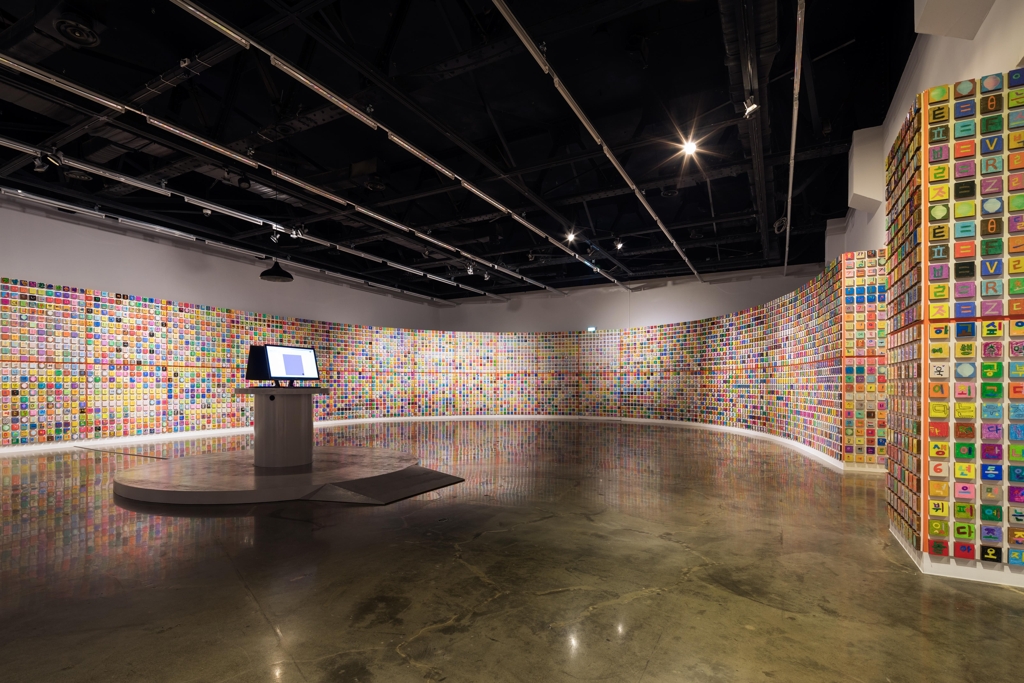

IV. A March of Imagination Toward an “Amazing World”

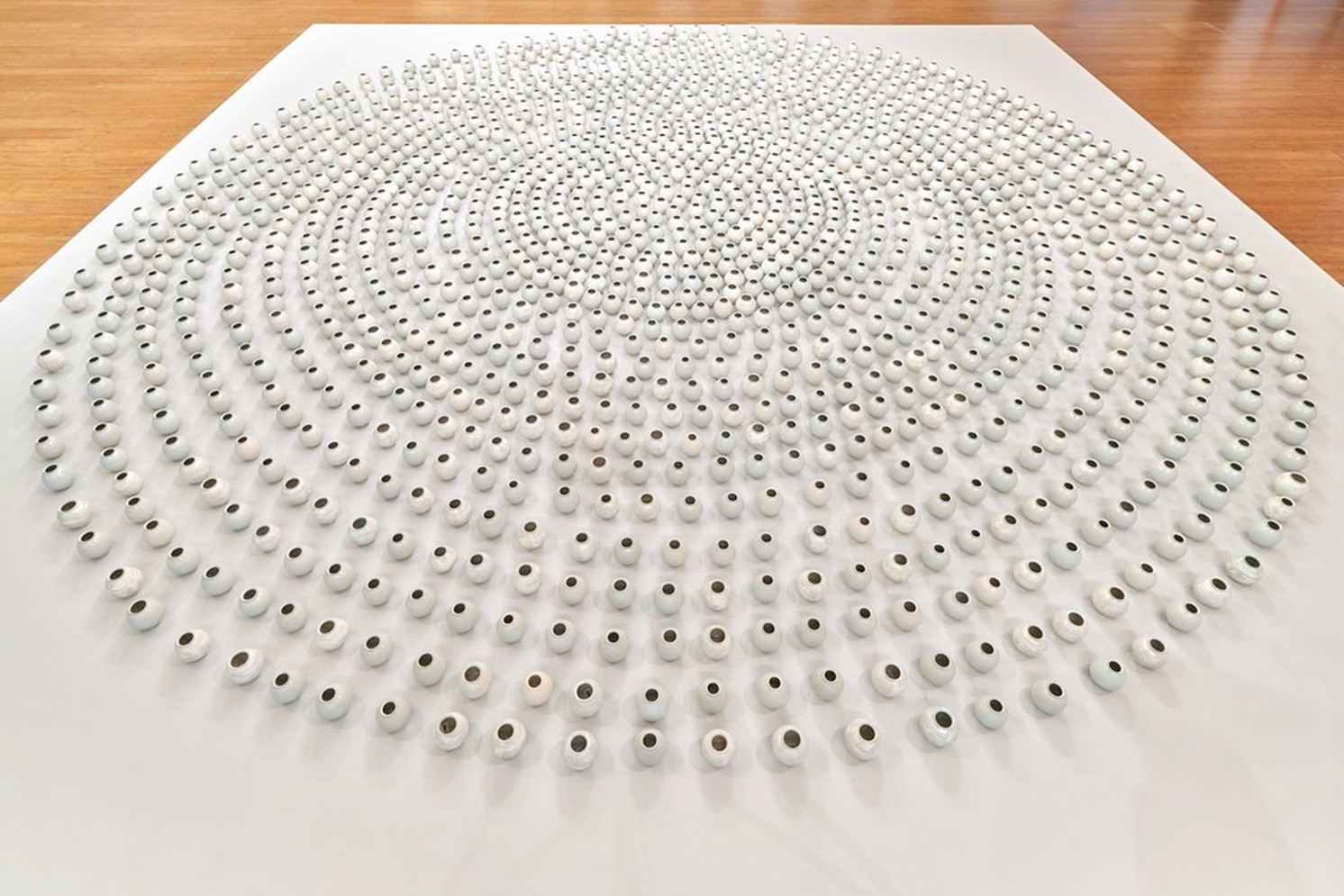

Kang’s

installations astonish viewers with their agile imagination. Like seeds growing

into vast fields, they result from viral proliferation. Just as Kang pursued

his dream in the U.S. through relentless effort, his tens of thousands of works

are products of collective participation and devotion. Without genuine care

from participants, even the noblest intention would remain hollow. In this

sense, Kang stands as an exemplary leader of collective creation.

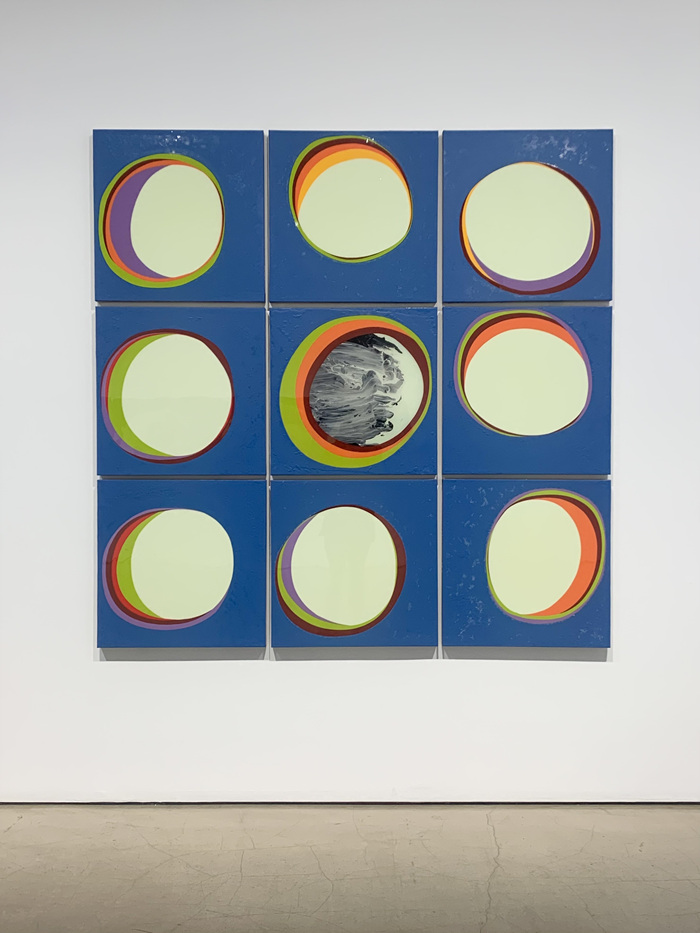

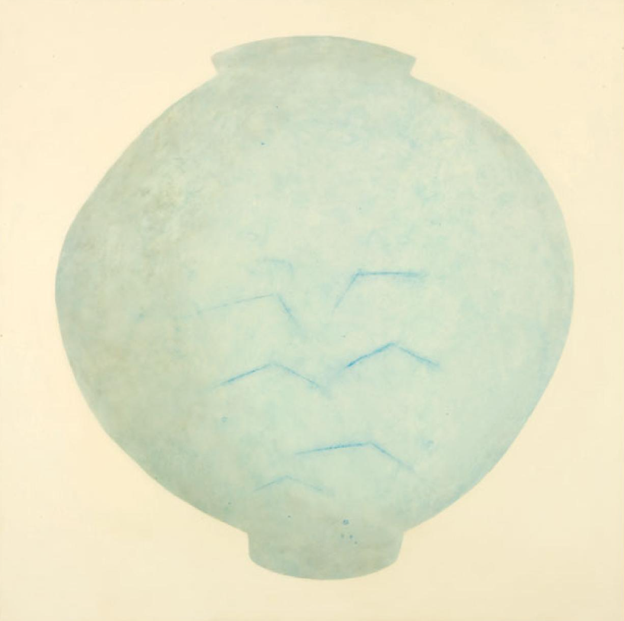

As

he ages, Kang increasingly gravitates toward Korean motifs, particularly moon

jars and Hangeul. Examples include works quoting Baekbeomilji and

the large-scale installation Moon Rising over Gwanghwamun (2007),

composed of 1.2-meter canvases. Texts such as “I wish Korea to be the most

beautiful country in the world, not necessarily the most powerful” reveal the

direction of his thinking.

Currently,

the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Gwacheon is hosting 《Ascending the Mountain: Multiple Dialogue》

(February 6, 2009 – February 7, 2010) to commemorate its 40th anniversary.

Installed on the ramp core wall beneath Nam June Paik’s The More,

The Better is Kang’s Samramansang,

composed of approximately 60,000 pieces—an homage to Paik, whom Kang regarded

as a father figure.

As

Kang himself notes, his work resembles bibimbap. In this traditional Korean

dish, rice forms the foundation upon which various ingredients are mixed. That

rice corresponds to the totality of “Koreanness” underlying Kang’s work—Korean

ways of thinking, history, customs, culture, and lived experience. These form

the viral core that drives the expansion of his art. Where these viruses will

head next remains unknown. Yet one already longs for the ecstatic ritual led by

Kang, helmsman of an endless voyage.

Notes

1. Juheon

Lee, Ik-Joong Kang, Marronnier Books, 2009, p. 13.

2. Jinseop

Yoon, “Culture and Bibimbap—On Ik-Joong Kang,” There Is No Threshold at

Museums, Jaewon, p. 113.