Held

at the Cheongju Museum of Art, 《Journey Home:

Ik-Joong Kang》 commemorates the 10th anniversary of the

administrative integration of Cheongju City and Cheongwon County. The

exhibition presents a wide range of works produced by the artist over the past

40 years, including Samramansang Happy World, the ‘Moon

Jar’ series, 1,000 Drawings, the Hangeul project Things

I Know, Uamsan, and Musimcheon.

When

a regional art museum selects an artist for a solo exhibition—particularly one

tied to a civic or commemorative event—it requires both political sensitivity

and consensus among stakeholders. Priority is often given to artists born in

the region, those who have demonstrably contributed to the local community, or

distinguished figures originally from the area who have built their careers

elsewhere.

In this sense, regional museums seek not only to present an

exhibition but also to amplify the cultural identity of the region through the

artist’s practice, often hoping for extended effects such as cultural tourism.

Amid the growing number of Korean artists active internationally, there is an

increasing preference for figures who embody both regional rootedness and

global recognition.

What,

then, does such an exhibition mean for the artist? Unlike a one-time solo show,

a retrospective that surveys an artist’s career over time plays a crucial role

in organizing and reassessing their artistic trajectory. A return-oriented

exhibition—one that evokes nostalgia through its very title—is particularly

meaningful in that it begins from the artist’s personal history. Information

such as birthplace, upbringing, education, and interpersonal networks may

appear secondary to artistic production, yet these elements provide essential

clues that open new critical interpretations of the work.

Accordingly,

this exhibition centers on three key points. First, it selects representative

works that have persisted throughout the artist’s 40-year career, allowing

viewers to reflect on the defining characteristics of Ik-Joong Kang’s practice.

Second, it interweaves past, present, and future by connecting multiple

temporal perspectives and thematic concerns. Third, it foregrounds Kang’s

origins in Cheongju, repositioning his regional and cultural context within the

broader narrative of his work.

From

a retrospective standpoint, this exhibition most strongly embodies the

characteristics of a survey among Kang’s past presentations. A significant

number of his representative works—produced shortly after his move to New York

and continuing to the present—are on view. Although the exhibition design is

not strictly chronological, the first floor presents newly commissioned

installations, while the second floor features earlier works, allowing viewers

to trace shifts over time.

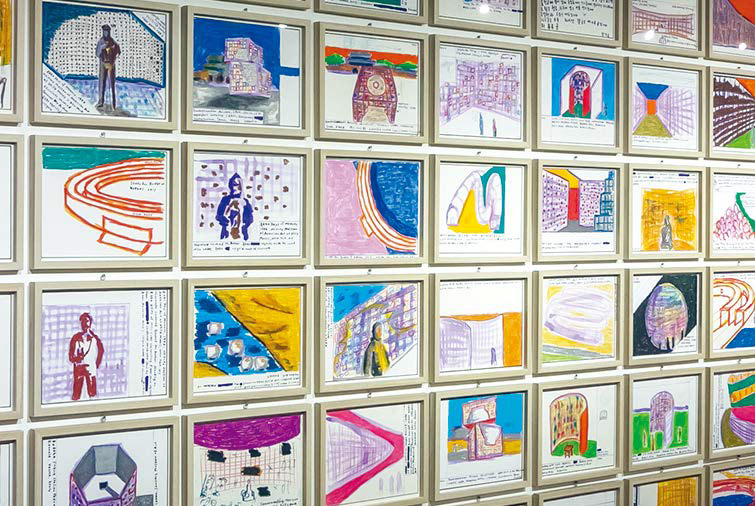

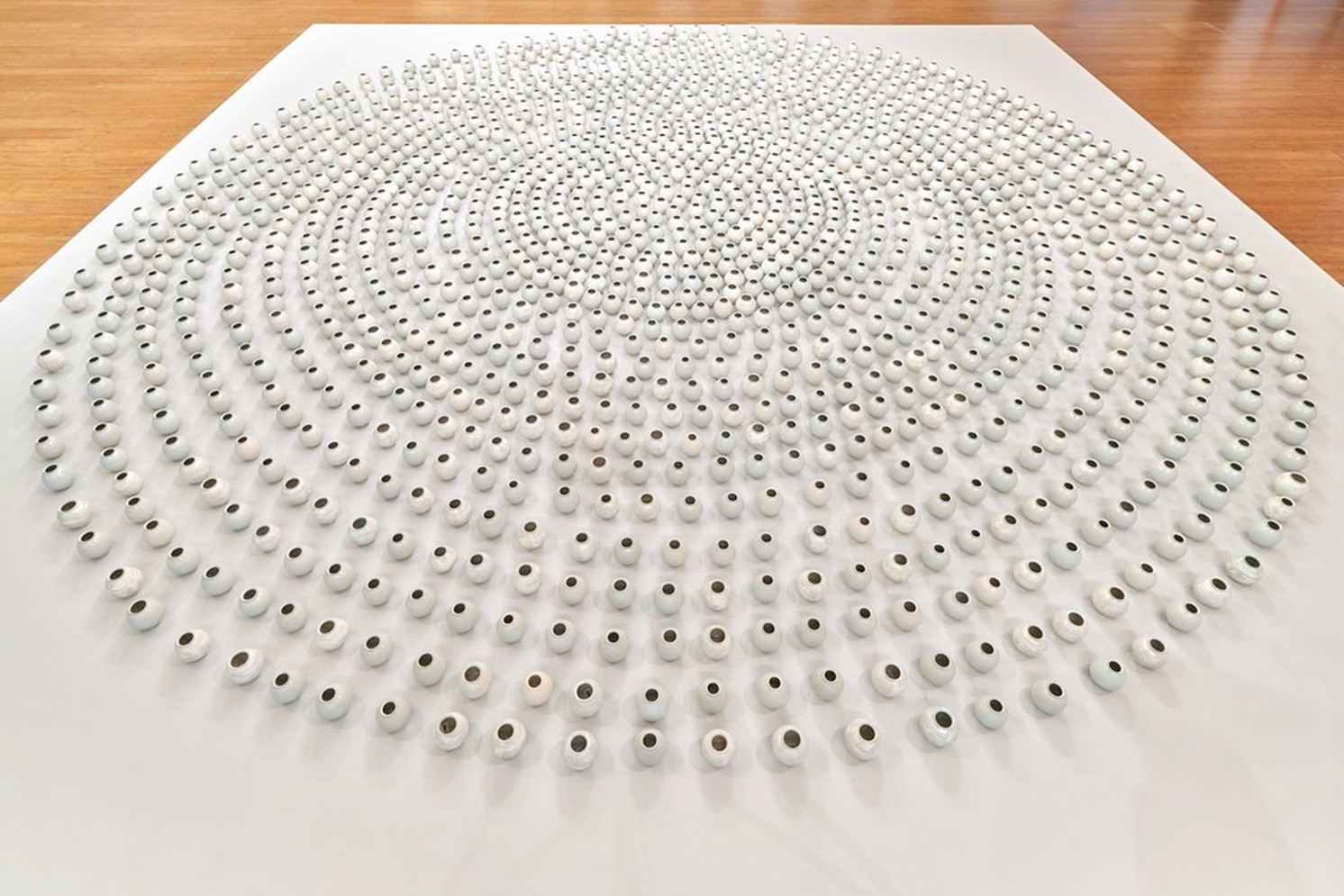

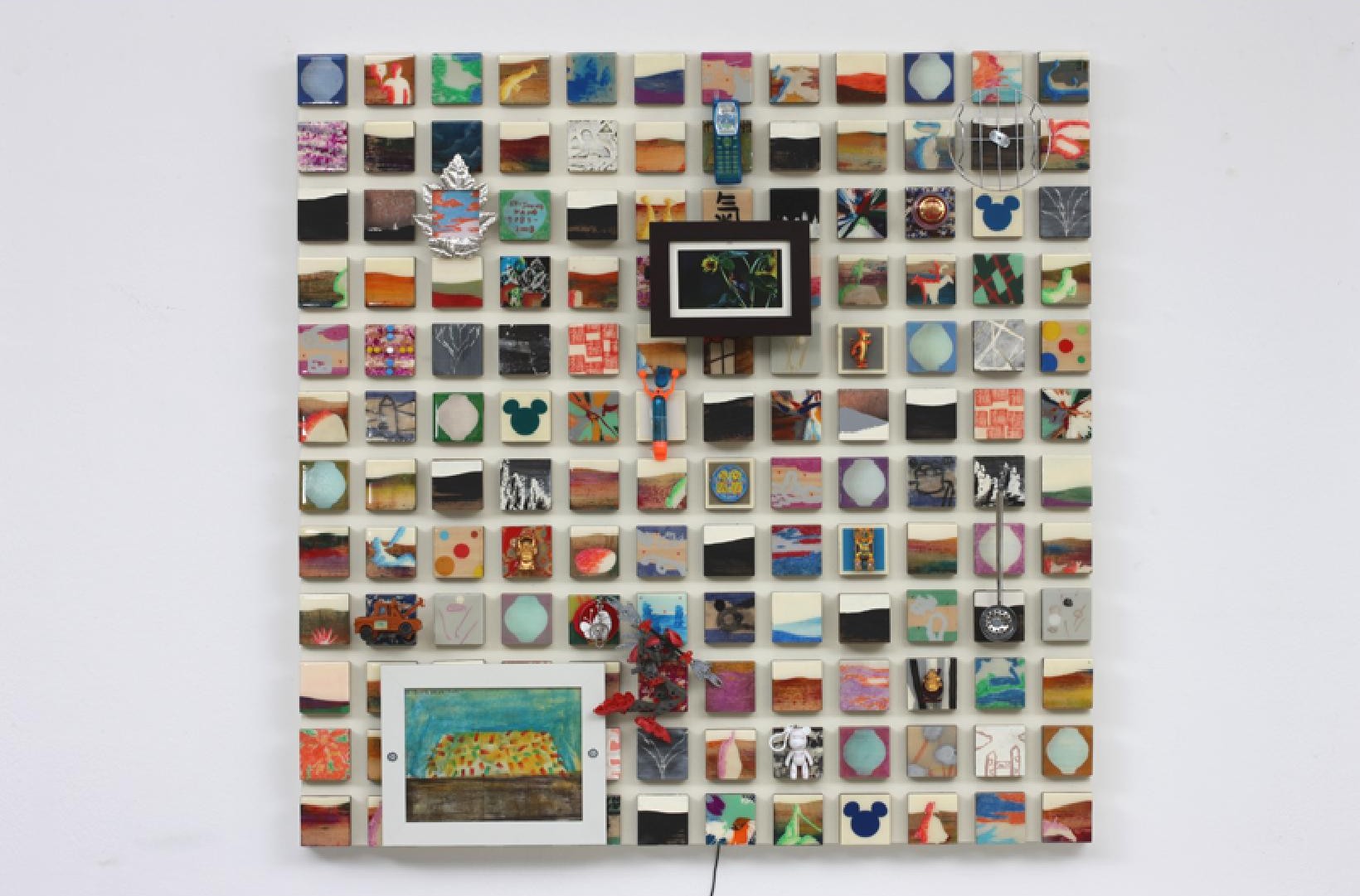

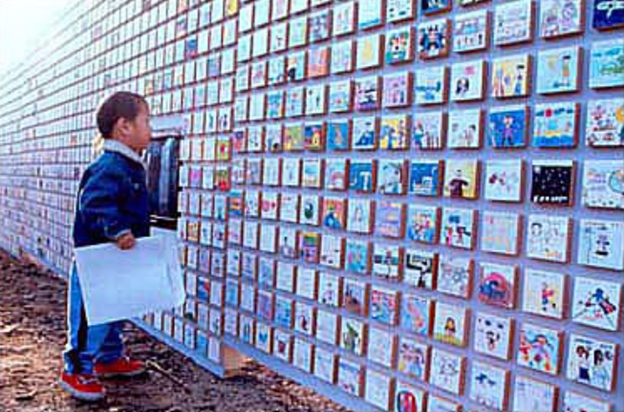

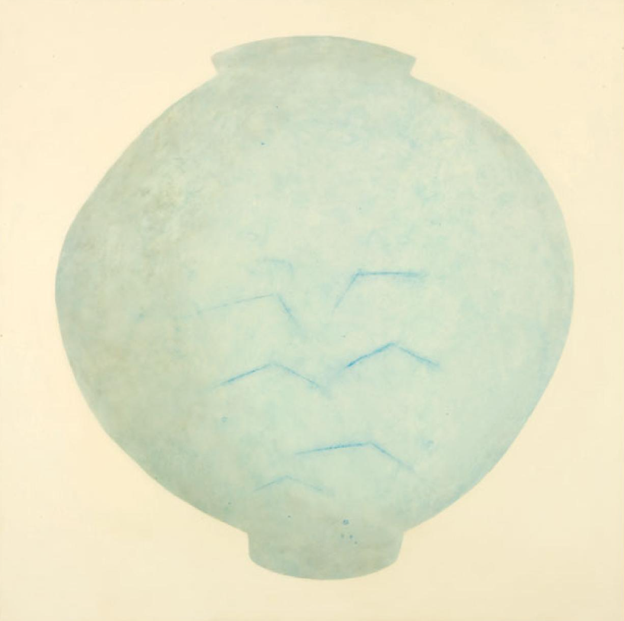

On

the second floor, key works from Kang’s New York period are displayed,

including Samramansang Happy World, composed of

approximately 10,000 three-by-three-inch canvases, along with objects and

paintings, as well as works from the ‘Moon Jar’ series. The small canvas format

was intentionally chosen to allow the artist to work continuously while

commuting by subway or bus in New York.

Kang’s method of assembling these small

units into large-scale installations tailored to specific spaces and themes is

well known. While each fragment carries its own meaning, their accumulation and

arrangement effectively visualize his enduring themes of harmony, connection,

communication, and coexistence. In this exhibition, nearly all works

demonstrate this logic of combination and amplification, revealing the origins,

present form, and stylistic completeness of his practice. The title Samramansang itself

refers to the totality of all things in the world, encapsulating this

worldview.

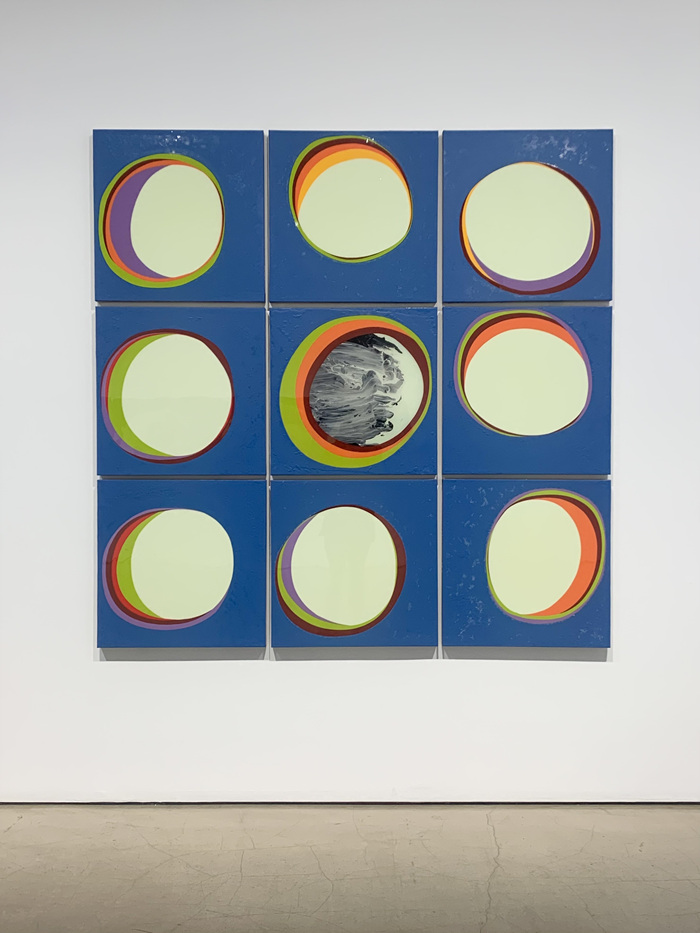

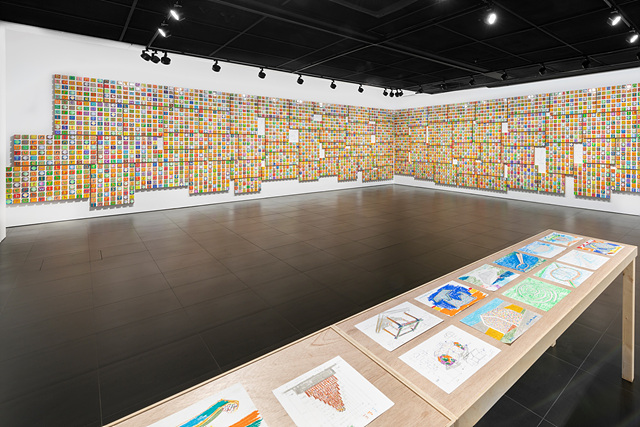

The

second major aspect of the exhibition is Kang’s approach to linking temporal

perspectives and themes. Works such as Samramansang Happy World,

the ‘Moon Jar’ series, and 1,000 Drawings, initiated in

the 1980s, are ongoing series that continue today. Rather than viewing time as

linear, Kang revisits earlier works by introducing new formal elements,

transforming their experiential and narrative dimensions.

In recent iterations

of 1,000 Drawings, scenes of everyday life observed

through television around 2024 are incorporated, with imagery framed to

resemble CRT monitors. By layering magazine pages as a base, attaching white

paper, and drawing over them, the artist emphasizes the pervasive influence of

media images that transcend borders, generations, and time. Although these

images originate from television broadcasts, they ultimately transform into

scenes that feel universally familiar.

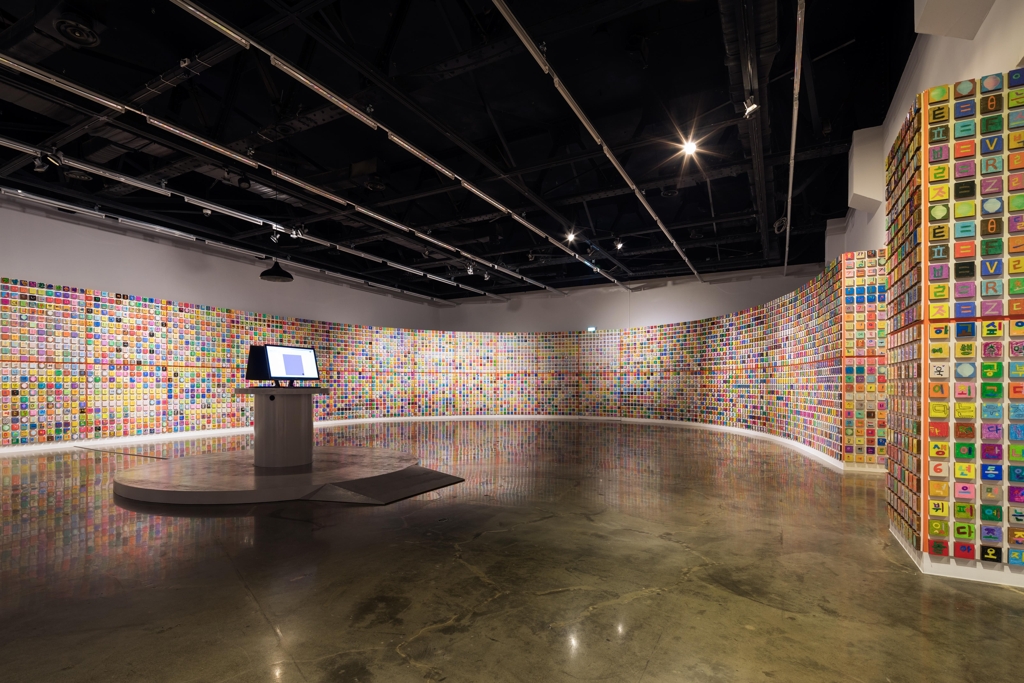

Notably, Samramansang

Happy World was presented with added lighting at the artist’s

request, so that the works would “shine like jewels in a jewelry store.” The

10,000 small blocks appear brighter than in previous exhibitions, accompanied

by sound that stimulates both visual and auditory senses, completing a

signature format unique to Kang.

The illuminated space, infused with street

noise, natural sounds, and human voices, evokes the dazzling world of

21st-century civilization. Installed within a 10-meter-high exhibition hall,

the Hangeul project Things I Know fills the space

with sentences composed of approximately 3,000 characters written since 2001,

containing fragments of life wisdom and diary-like reflections.

Originally

conceived to teach his son Hangeul by differentiating consonants and vowels through

color, the project simultaneously conveys familial affection and the artist’s

love for color as a foundational element of art. The sentences, written without

regard for spacing—despite Hangeul’s sensitivity to spacing—flow continuously

in a single line.

In this exhibition, the addition of a child’s voice reciting

the text transforms the gallery into an immersive environment. The interaction

between visual and auditory language recalls Kang’s early experiences learning

English in New York, while the dense field of characters evokes both the Tower

of Babel and the Buddhist concept of “form is emptiness, emptiness is form.”

In

an interview with Katherine Anne Paul, curator of Asian Art at the Birmingham

Museum of Art, Kang speaks of recalling his mother when thinking about his

hometown, suggesting that the human soul is fundamentally connected through

maternal memory. Reflecting this sentiment, the artist handwrote poems directly

onto the museum walls.