Solo Exhibitions (Brief)

Kang has presented major solo

exhibitions and public art projects across Korea, the United States, and Europe

since the late 1980s. Notable solo exhibitions and projects include 《Four Temples,

Forever Is Now》(The Great Pyramid of Giza, Cairo,

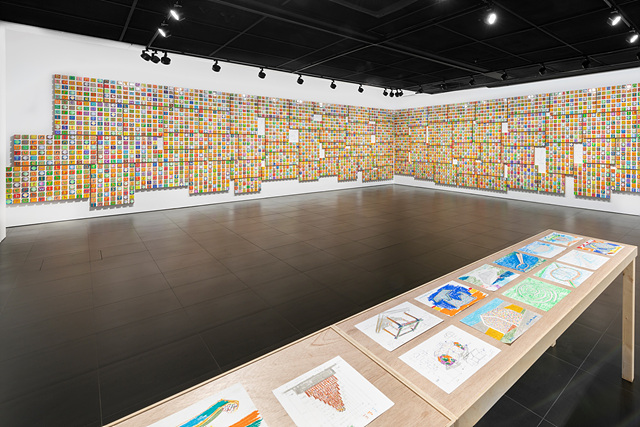

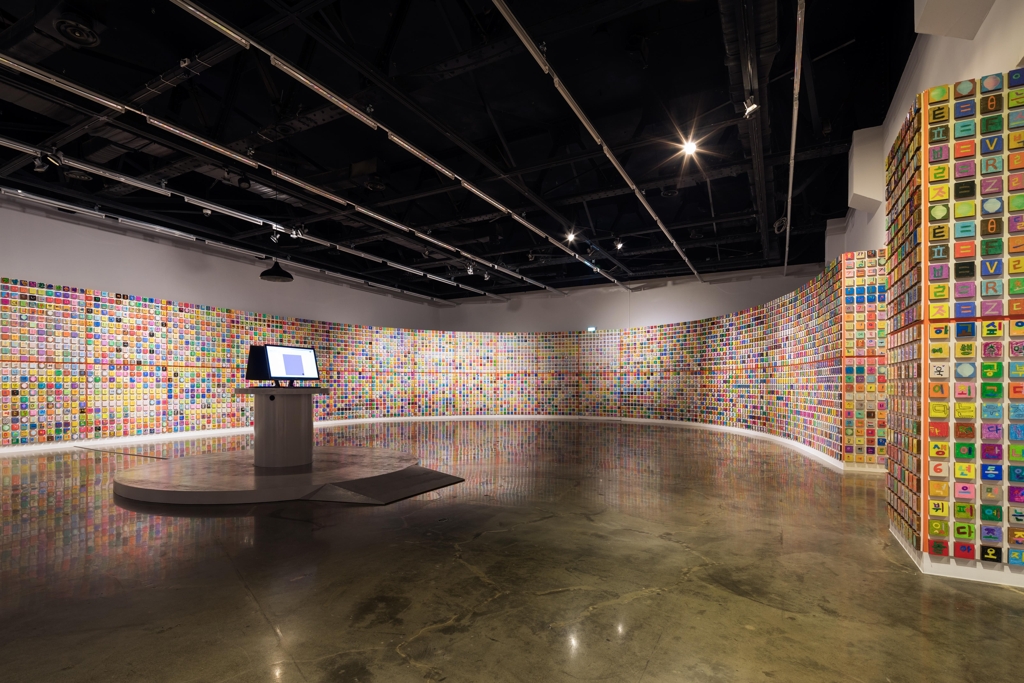

2024), 《Hangeul Wall and 40-Year Retrospective

Exhibition》(New York Korean Cultural Center, New York,

2024), 《Journey Home》(Cheongju

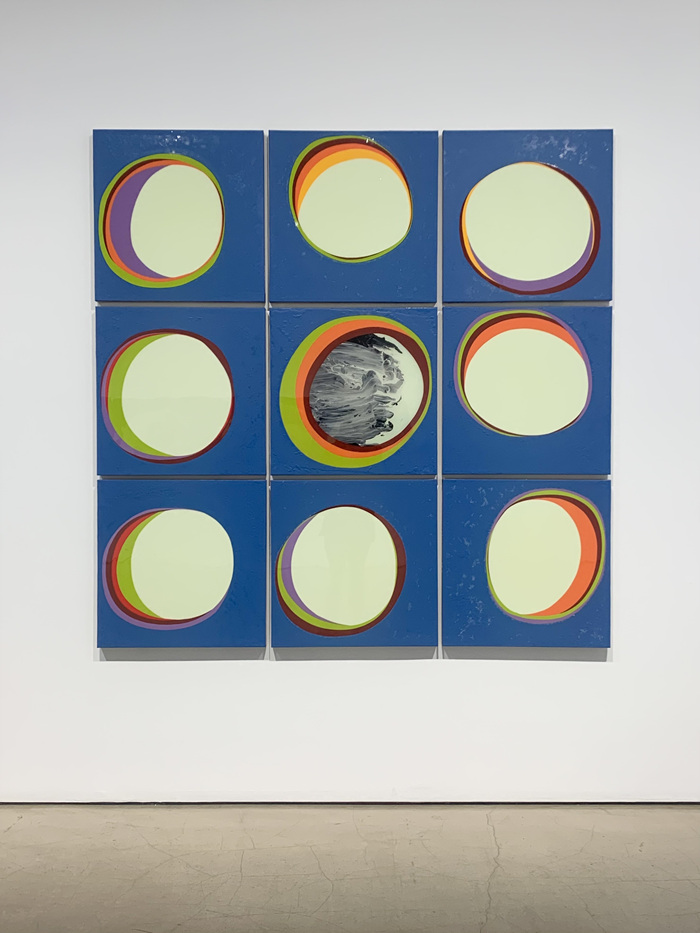

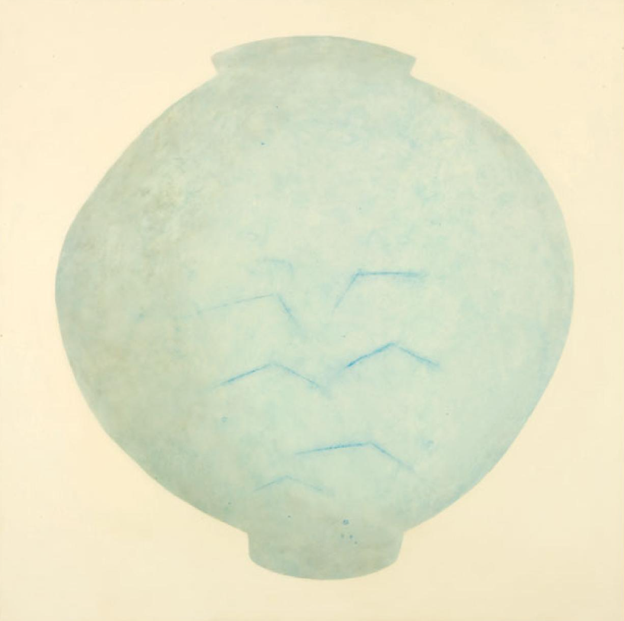

Museum of Art, Cheongju, 2024), 《The Moon is Rising》(Gallery Hyundai, Seoul, 2022), and 《Gwanghwamun

Arirang》(Gwanghwamun Square, Commissioned by the

Republic of Korea, Seoul, 2020).

Internationally, Kang has held solo

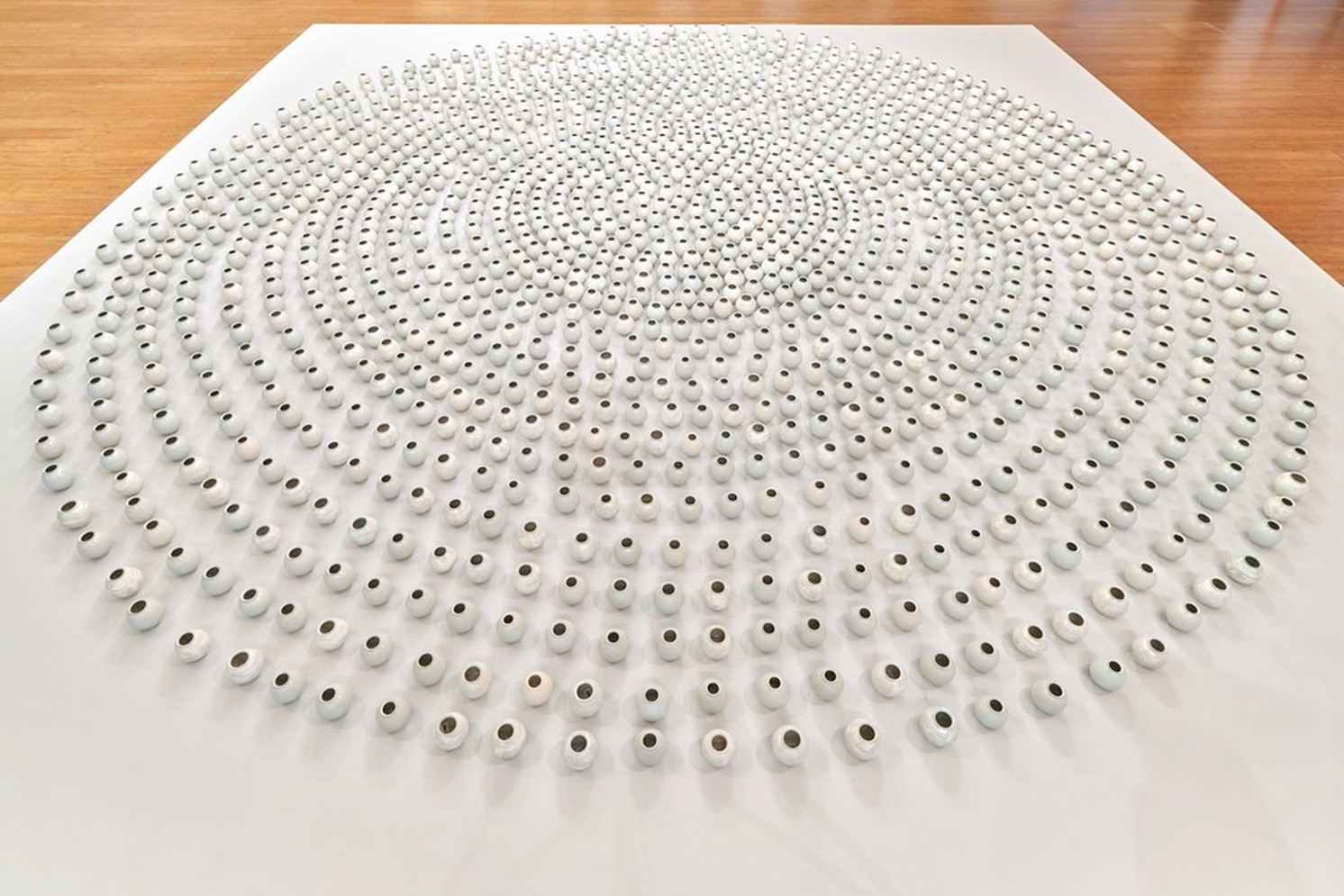

exhibitions such as 《Moon Jars》(National Gallery of Art, Sofia,

2017), 《Floating Dreams》(River

Thames, London, 2016), 《The Moon Jar》(Robilant and Voena Gallery, London, 2016), 《Floating Moon Jars and Mountain and Wind》(Museum

of Modern Art, Kuwait, 2015), and 《25 Wishes》(Korean Gallery, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2010).

Group Exhibitions (Brief)

Kang has

participated extensively in major group exhibitions at national museums,

international biennials, and leading global institutions since the 1980s.

Notable exhibitions include 《MMCA Collection: Korean

Contemporary Art》 (National Museum of Modern and

Contemporary Art, Seoul, 2025-2026), 《Every Island is a

Mountain》 (Palazzo Malta, Venice, 2024), 《The Art of Our Time: Master Pieces from the Guggenheim Collections》 (Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao, 2015), 《Contemporary

Korean Ceramics》 (Victoria and Albert Museum, London,

2017), and 《Reshaping Tradition: Contemporary Ceramics

from East Asia》 (USC Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena,

2015). He has also been invited to major international biennials, including the

Venice Biennale (1997), the Gwangju Biennale (1997, 2004), and the Buenos Aires

International Biennale (National Museum of Arts, Buenos Aires, 2002).

Awards

(Selected)

Kang received

the Special Merit Award at the 47th Venice Biennale in 1997, along with the

Louise Comfort Tiffany Foundation Fellowship and the Ellis Island Medal of

Honor. He was also awarded the Korean Art and Culture Award (Presidential

Award) in 2012 and the Sejong Cultural Award in 2021, marking significant

recognition of his contributions both internationally and in Korea.

Awards

(Selected)

Kang’s work has been included the collections

on numerous major art institutions in Korea and abroad, including the

Guggenheim Museum (New York); the British Museum (London); the Whitney Museum

of American Art (New York); the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; the

Museum of Fine Arts Boston; the Museum Ludwig (Cologne); the National Museum of

Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea (Seoul); the Seoul Museum of Art; the

Gyeonggi Museum of Modern Art (Ansan), and the Leeum Museum of Art (Seoul).