What

once stood as a temporary wall has now been laid on its side to serve as a

pedestal, leaning against which are a few diminutive objects.

Accordingly,

one’s gaze must lower below eye level, and then look across. Some objects

prompt the viewer to shift their vantage point. In the act of bending down to

see what is placed low and rising again to walk around, the body may experience

the freedom of movement, relishing a continuous and rhythmic sensation of

motion. Yet, within that flow, there are moments of leap. When approached

closely enough, Dajeong Jeong’s palm-sized sculptures reveal themselves as

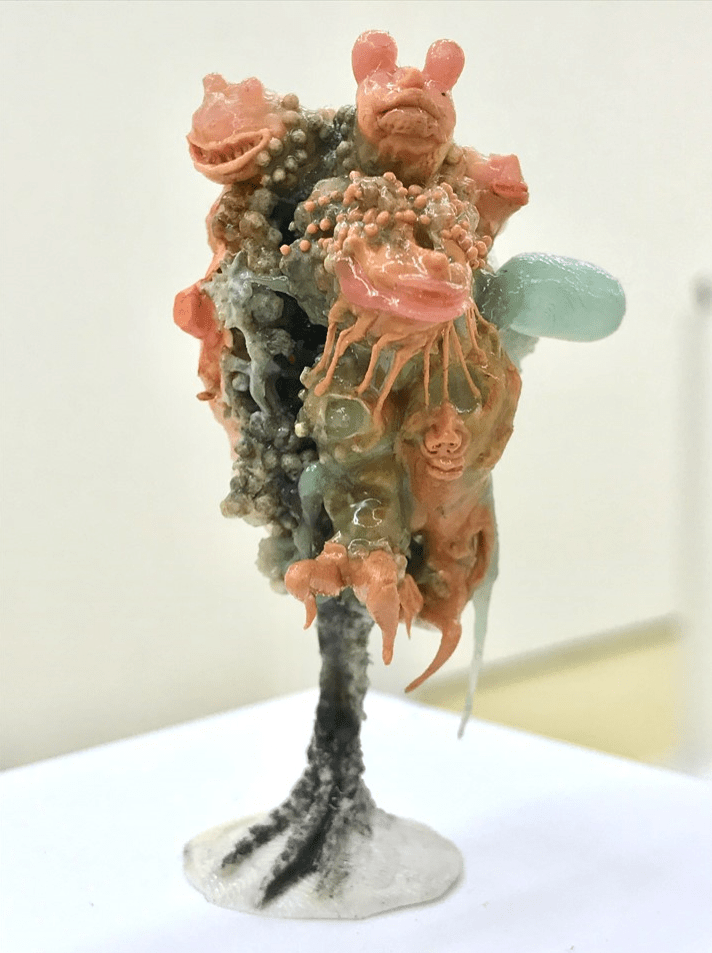

miniature stages where her memories are enacted and transformed. Similarly, Ham

Jin’s sculptures, mere smudges at first glance, extend protrusions to unveil a

monstrous vitality.

Dajeong

Jeong constructs specific scenes by layering images of places seen on maps with

memories of physically visiting those sites, combining industrial metal goods

and natural objects. This process includes stepping back from something too

emotionally or physically close to observe it from a distant, surveying

perspective, and then approaching it again to enlarge or reduce it based on how

it is sensed. Unlike maps that schematize topographical relationships in

precise proportions, the scenes she fabricates sometimes present an absurd

scale—a ground too narrow, a dried flower branch absurdly magnified. In recent

works, she has begun using plaster instead of plywood: small sculptures rest on

concave panels, or conversely, solid panels overlay fractured fragments.

Layering one material atop another, she experiments at the most fundamental

level of form. This practice of juxtaposing and stacking disparate materials

and perspectives may be a way of interrogating the density—or hardness—of the

time and space we inhabit.

In

his first solo exhibition "Imaginative Diary"—which also marked the

opening of Sarubia—Ham Jin inserted miniature scenes into the cross-sections of

carved toy figures, and joined together tiny body parts sculpted from clay to

construct bizarre forms. These tiny creatures were placed in the holes of

charcoal briquettes, on the fringes of objects, or nestled in cracks throughout

the exhibition space, enacting imaginary situations. Later, these micro

clusters evolved into more abstract formations that migrated to the surface of

individual pieces. At times, he molded large black sculptures using polymer

clay—his primary medium—each resembling a city or a planet. At others, he

created smaller figures again: non-human forms engulfed by an overgrowth of

organs. As seen in the trajectory of his practice—and in his comment that he

doesn't quite understand the difference between large and small—the artist

known for "miniature" sculptures is not merely dealing with scale.

His recent small sculptures take on egg-like forms, where abstract organic

shapes are intertwined and condensed. These small eggs connect expansively with

the surrounding space and surface, continually withholding a part of themselves

from being fully grasped at once.

Both

artists' works distort the scale of the time and space the body inhabits,

inviting viewers into other worlds. Yet, the exhibition does not tell the story

of mutually exclusive parallel realms. Dajeong Jeong applies plaster directly

onto the gallery walls, confronting viewers with the foundational surface of

her work. Pigments that flow beneath her floor-placed sculptures solidify

ambiguously, extending the boundary between work and space. Fragments of

plaster panels, which could have served as alternate stages, are caught in nets

in the corners of the gallery. The powder-like debris of even more fragmented

works fills the narrow molding gaps near the floor. Likewise, Ham Jin's

sculptures, no longer confined to individual pedestals, are arranged separately

or together on a larger platform, mindful of their interrelations. Some hang in

midair, closely engaging with the gallery’s background space. Beneath the

plaster painting by Dajeong Jeong that spreads across the wall visible

immediately after descending the stairs, Ham Jin’s sculpture is placed, forming

a point of contact between the two artistic worlds. Once given physical form, a

work can no longer remain merely within memory or imagination; it must unfold

its own life within the space.

Even

if we hold onto the pure belief that every work is its own small world, what we

ultimately experience in the exhibition is the sense of transition between

different worlds. The body repeatedly enters and exits small worlds. This world

implies something about that world, and that world in turn about this one.

Perhaps passing through all these worlds is, ultimately, a way to return—again

and again—to the world we live in. But who are we, and where is this place? The

works of both artists prompt us to reacquaint ourselves with the ground upon

which we cast our gaze, and the surfaces on which we stand and move. That

subject might be tiny or immense, and that ground might be incredibly fragile

or unexpectedly solid.

Lee

Junhyeong | Intern Curator at PS Sarubia